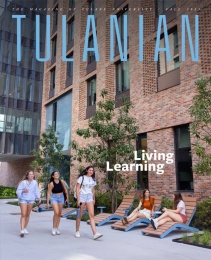

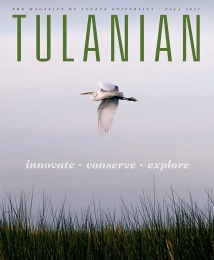

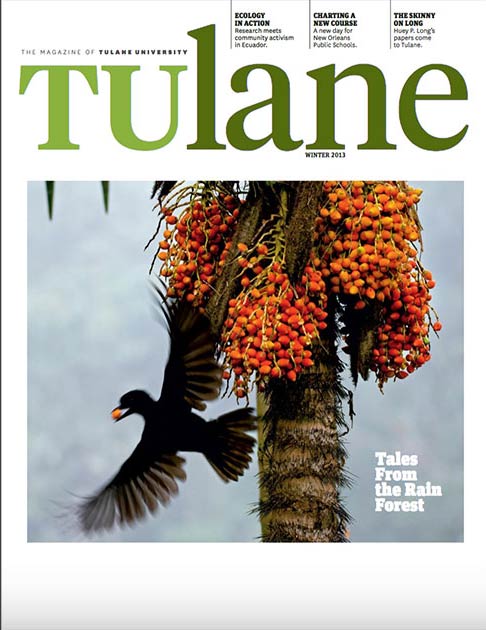

Wildlife Photos by Murray Cooper. Photos provided by Cece Acosta, Catie Mae Carey, Jordan Karubian and Treasure Joiner. Above: Madelyn Seward and fellow TIERA Scholars hike on the FCAT reserve.

The Chocó region of South America, nestled between the Andes Mountains and the Pacific Ocean, is one of the most biodiverse places on Earth.

It receives an average of eight meters of rainfall each year, more than twice the amount in many parts of the Amazon Rainforest. It’s situated on the equator, spanning from southern Panama into northwestern Ecuador, surrounded by drier regions, and shared by a massive number of endemic species found nowhere else on the planet. The region is of great interest to conservationists hoping to preserve the natural habitat and reverse decades of deforestation.

It is to this unique place that Tulane students travel as part of the Tulane Interdisciplinary Environmental Research & Action (TIERA) Program — the result of a relationship between Tulane and Fundación para la Conservación de los Andes Tropicales (FCAT), an Ecuadorian NGO focused on grassroots research and conservation.

Students in the program participate in a two-week immersive field trip at the FCAT field station over the summer, usually between their sophomore and junior years. They work in groups on ongoing, community-engaged projects that range from water quality and bird diversity to art and social attitudes about conservation.

After the field course, students can apply to be a TIERA Scholar and independently develop a project of their own. If chosen as a TIERA Scholar, these students first take a course in research design, where they work with a faculty advisor and a partner at FCAT to co-design their research and apply for grants, before conducting their research the following summer.