(Photography by Paula Burch-Celentano)

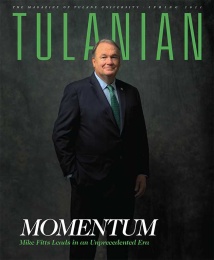

Spirit of Tulane

The Spirit of Tulane Research Award recognizes individuals whose work embodies Tulane’s motto: Non sibi, sed suis (Not for one’s self, but for one’s own).

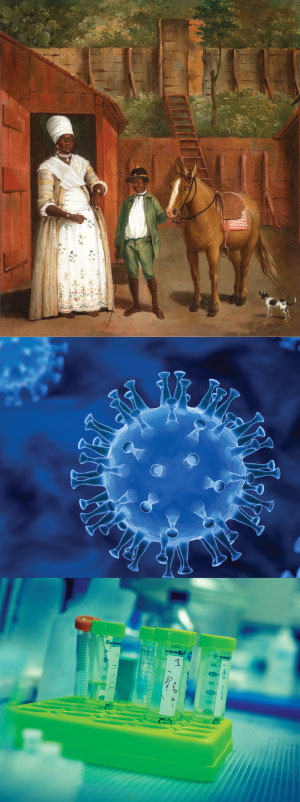

At the inaugural Research, Scholarship and Artistic Achievement Awards gala in November 2021, the Spirit of Tulane Research Award was awarded to an art historian of the African Diaspora, a physician-scientist and an immunologist. The Tulane Research, Scholarship, and Artistic Achievement Awards are to be given annually to honor outstanding scholars and to recognize exceptional research achievement and impact on advancing knowledge in science, engineering, health and education, or creativity in the arts, the humanities and other academic fields of study.

Mia L. Bagneris

“Art history is my method, but Black studies is my discipline.”

That’s the take of Mia L. Bagneris, associate professor of art history and director of the Africana Studies Program at the School of Liberal Arts. Bagneris focuses on African Diaspora art and studies of race in Western art.

Bagneris earned her undergraduate, MA and PhD degrees from Harvard University. She joined Tulane’s Newcomb Art Department in 2009.

If any young Black girl from New Orleans was destined to be an art historian, it was Bagneris. Her mother, Althea Leonard Foster, earned a Master of Arts in art history from Tulane in 1994.

“I grew up at the New Orleans Museum of Art to the point where security guards knew my name,” said Bagneris. “I’ve always loved museums. I have a second-grade journal, where I wrote something like, ‘When I grow up, I want to be an impressionist and impressionists are artists who paint with light.’”

Bagneris said, at Tulane and in the discipline more generally, “I’m trying to build an art history where people who look like me and have the interests that I have, feel like it is a field that they can work in and build careers in and use to effect change.”

Her scholarship centers on representations of people of color, specifically people of African descent, in British and American art more than a century ago. In her teaching, she strives to open her students’ eyes to “connect what they are learning about the past to what they see today.”

“Art history is my method, but Black studies is my discipline.”

Mia L. Bagneris

Her latest publication, “Miscegenation in Marble: John Bell’s Octoroon” (The Art Bulletin, 2020), drawn from her current book project, Imagining the Oriental South: The Enslaved Mix-Race Beauty in British Art and Culture, c. 1865–1900, explores this case in point.

John Bell was a 19th-century British sculptor who never set foot in New Orleans. But he imagined life in Louisiana and romanticized, as did several British artists of that time, the ideal of an “enslaved mixed-race beauty.”

Bagneris’ first book, Colouring the Caribbean: Race and the Art of Agostino Brunias, explores similar themes, as well as the role of visual images, more generally, in constructing race in the 18th-century British West Indies.

Bagneris also works on 19th-century Black artists and is co-author of a work in progress, Beyond Recovery: Reframing the Dialogues of Early African Diaspora Art History & Visual Culture, c. 1700–1900.

Bagneris said that her goal, as director of Tulane’s Africana Studies Program, is to build a vibrant and thriving Black studies department that becomes a regional and eventually national hub for the discipline. The program has recently secured funding from Tulane’s Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Initiative Committee for a three-year pilot program dedicated to building an intergenerational Black studies scholarly community that will support bringing prominent Black studies scholars to Tulane; provide scholarships for students to study abroad in Africa; and offer undergraduate research fellowships for students to work with faculty mentors.

“Building this program is part of my dream,” said Bagneris. “I am committed to it.”

Dr. Gregory Bix

Right before Mardi Gras in February 2020, Dr. Gregory Bix traveled to attend the International Stroke Conference in Los Angeles. From California, he flew to Brisbane, Australia, to work with colleagues at Queensland University of Technology.

Prior to his flight back to New Orleans, he was closely questioned about his travel plans and his next of kin. He knew something serious was up.

Then, everything shut down due to the pandemic.

“I realized the same therapies that I was developing for dementia are also clinically relevant to the virus.”

Dr. Gregory Bix

“I started thinking, what am I going to do? I can sit back and say, ‘Woe is me,’ or I can think about how I might be able to help and make a difference,” Bix said.

He did not sit back.

Bix had joined the Tulane School of Medicine in fall 2019. He is a professor of neurology, holder of the Vada Odom Reynolds Chair in Stroke Research, and director of the Clinical Neuroscience Research Center.

With a desire to facilitate better communication among Tulane researchers, he organized CREST (COVID-19 Researchers at Tulane), a group open to anyone at the university who “has any interest in clinical, translational or basic research related to COVID-19.” CREST began meeting every couple of weeks and continues to meet today.

Through CREST, Bix saw the need for a biobank to collect tissues from coronavirus patients and make these samples available for future research. By summer 2021, he had established COBALT (COVID-19 Biobank and Library), safely storing hundreds of biological samples.

Top image: A Mother With her Son and a Pony, by Agostino Brunias

Long COVID-19 is especially poorly understood, said Bix. Patients get sick from the coronavirus and seem to recover but then have long-term neurological problems such as forgetfulness, brain fog, headaches and fatigue. Bix and Dr. Michele Longo, assistant professor of neurology, started the Long COVID Clinic to help these patients. “People are coming in, they want help, they want answers,” said Bix.

For Bix, an “aha” moment occurred early in the pandemic when he was reading about the virus. He speculated that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, was binding to a cell receptor, called an integrin, which he had been studying in his work on vascular dementia.

“That was the spark,” he said. “I realized the same therapies that I was developing for dementia are also clinically relevant to the virus.”

When he learned that COVID-19 infection can cause strokes, Bix pivoted his vascular dementia research to concentrate on the coronavirus. He has collaborated with Angela Birnbaum, director of biosafety and biocontainment, and others to help generate supportive data and file an application for a U.S. patent for a COVID-19 therapeutic. He already has several patents related to stroke treatment.

Bix is grateful to work on alleviating the effects of COVID-19. He’s thrilled to be at Tulane, where he was given encouragement to follow his instincts. Leaders such as Dr. Giovanni Piedimonte, vice president for research, told him, “You have this idea, go for it.”

“I’ll never forget that support,” said Bix.

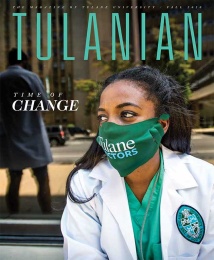

Monica Vaccari

“It’s coming! It’s coming!” That’s how Monica Vaccari sounded the alarm about the pandemic to her new colleagues in February 2020.

Vaccari had joined the Tulane National Primate Research Center (TNPRC) and the School of Medicine that month as a faculty member in the Division of Immunology and an associate professor of microbiology and immunology.

A native of Italy, Vaccari was monitoring closely what was happening with novel coronavirus cases in her home country, where her parents live.

“I was on high alert,” said Vaccari. “I was constantly looking at Europe and China.” She knew the wave of the pandemic would soon be in the United States.

At that time, lots of people were sick and dying in Italy. “We knew what it was. But we had no idea how to stop it. There was no prevention, and it was spreading.”

“I want to make a dent in diseases that I’m studying.”

Monica Vaccari

Vaccari came to Tulane from a position at the National Institutes of Health in Washington, D.C.

It was serendipitous that Vaccari had been recruited to the primate center. Jay Rappaport, TNPRC director and chief academic officer, and others at the center were already doing urgent planning to study the virus and the disease. Rappaport and the team proactively sought to obtain SARS-CoV-2 live virus to study it using their unique facilities and expertise.

The TNPRC was among the first institutions approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to receive the viral stock. And its researchers, including Vaccari, jumped ahead to do early studies, supported by Tulane, even before federal grant money was available — a bit of a risk.

Rappaport prioritized developing an animal model of the coronavirus that simulates how the disease affects the human body. COVID-19 research soon became the primary focus of the primate center.

Vaccari immediately began to study early host immune responses to SARS-CoV-2. By December 2020, she published a study in Nature Communications that shows that having a robust initial immune response to coronavirus infection might be detrimental in fighting off the virus.

After 15 years investigating HIV vaccines using nonhuman primate models, Vaccari was well prepared. “Each virus wants to survive,” said Vaccari, “and they will do what they can in your body to try to replicate and survive. Each virus evolves not to kill the host because they will lose. They don’t want to kill you.”

But viruses do sometimes kill when they hijack immune systems. As Vaccari hypothesized and then proved, some immune systems respond to the coronavirus in a “dysregulated fashion.” They respond with a cytokine storm of excessive inflammation. The immune system is “doing too much. And then in the end, it is killing you instead of killing the virus.”

Vaccari has a passion for the complex immune system and its reactions. The immune system is “always evolving. It’s never boring. Every few months, we discover new molecules, new cells, new avenues,” she said.

“I want to make a dent in diseases that I’m studying,” she added. She is continuing her work on COVID-19, involved in research that delves further into the illness’s inflammatory symptoms. She’s also looking at therapeutics and the development of vaccines with longer efficacy. She’s building up her laboratory and teaching graduate students.

For Vaccari, Tulane’s motto “not for one’s self, but for one’s own” is “a sophisticated way of saying that we are doing research for health — and that benefits everybody. It’s beautiful that we put it in the spirit of Tulane.”