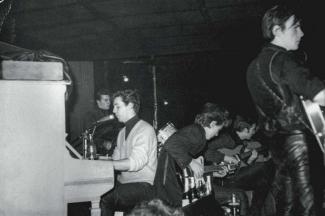

He suggested that we go to a club nearby, where, he said, a good English rock ’n’ roll band was playing. I was dubious. After all, I’d been raised on rock ’n’ roll, from Alan Freed to Poppa Stoppa, and had just spent two years in one of its cradle cities. The place was called the Top Ten and was suitably seedy, which was nothing new to me after Decatur Street, where in those days the aroma of malt from the Jax brewery settled over sailors’ bars.

We walked into a room of smoke and music. Five men, about our age, were on the stage. In their leather jackets and jeans, with DA haircuts, they looked most like the tough kids I’d known in high school. I know now that it consisted of John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Stuart Sutcliffe playing guitar and Pete Best on drums.

But the music! It was the rock ’n’ roll I’d grown up on, from Eddie Cochran to Ray Charles and Carl Perkins by way of Little Richard, with “Bésame Mucho” thrown in for a breather. Linda and I, of course, were way overdressed for a rock club, Linda in heels and me in coat and tie, the standard JYA uniforms of that era.

After they played Gary U.S. Bonds’ song “New Orleans,” I told Linda we should talk to them; after all, they looked to be our age, and I was curious as to how and why they were playing American music and doing it so well. She demurred, and I understood. We were expected to be upright young Americans, and seemingly the only thing upright about the band was their position on the stage.

We stayed for a couple of hours, and I’m not sure I remember them taking a break. I left exhilarated, tired from the dancing, and by the time we got back to Paris a week or so later, I’d stored the evening’s events among my memories.

I’m not sure when I first heard Beatles records. It may have been 1963, when Beatlemania struck Britain, or 1964, when it exploded in the U.S., most famously on the “Ed Sullivan Show.” At first I didn’t make the connection; after all, original songs were not part of their Hamburg repertoire. But then as I heard their recordings of “My Bonnie” and, yes, “Bésame Mucho,” I began to guess.

The first blow-by-blow history of the group came out in 1967 or ’68, and it listed all the dates and places they’d played, from Liverpool to Hamburg and beyond. On the April night we’d been there, they had indeed played the Top Ten. At the time, I had the ticket from the club, and I remember pulling it from my carefully chronological collection of receipts and staring at it with a bit of awe. Alas, I haven’t seen the ticket since 1976. It lived in my steamer trunk, but that’s long since gone, though most of its contents are in a box in my garage.

Years later, I told Linda who it was that we’d seen, and she didn’t remember the club or the band. She couldn’t wait to tell her eldest son, who was a Beatles fanatic.

I have always retained the fantasy that we did talk with them, that they visited us when they came to Paris later that year, that I hit it off best with John (of course), that I visited them in Liverpool when I traveled to England before returning home, that John and Paul came to visit me in Los Angeles when they played the Hollywood Bowl. Hard to believe that only one of those who became the Beatles we know — Paul — remains. Best is still alive but is an unfortunate (and bitter) footnote. John and Stu, the two closest friends, are both gone, and so is George. But here I am 60 years later, and I’m still obsessed with the two hours or so I spent in a club in Hamburg.

In memory of Linda Prager (NC ’62), 1941–2011.

Joel R. Gardner is a writer and oral historian based in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. He has degrees in French (from Tulane) and journalism (from UCLA), and his publications range from books and scholarly articles to restaurant and music reviews.