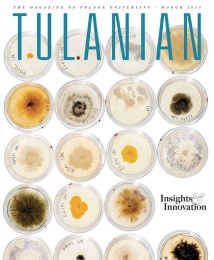

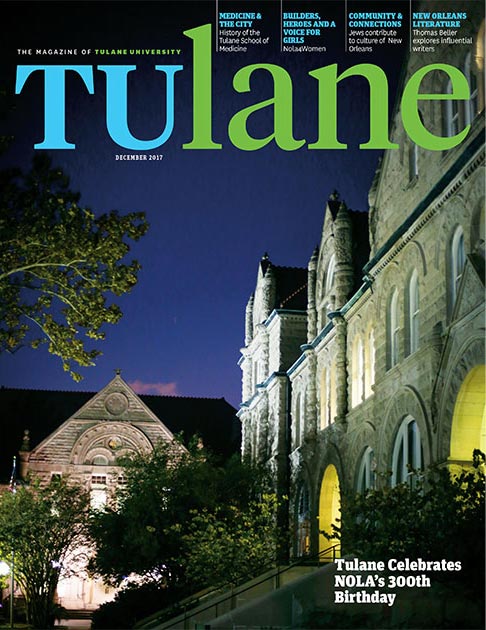

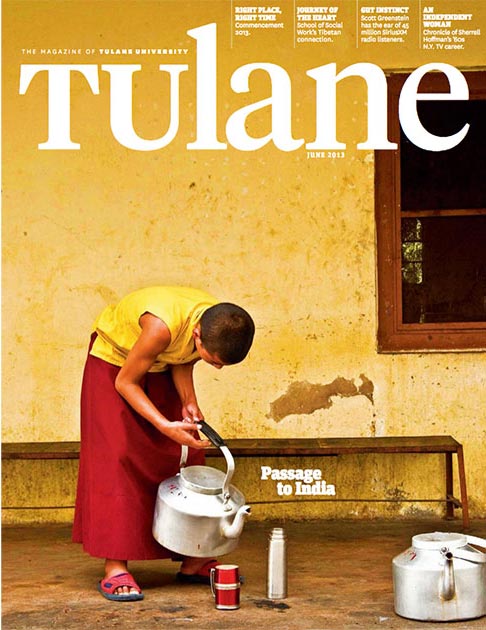

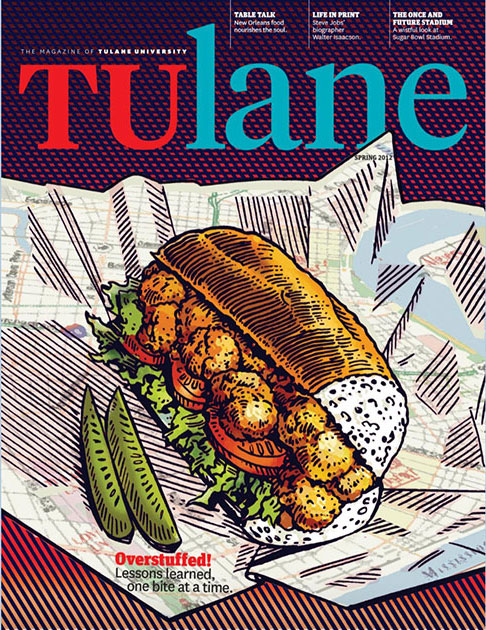

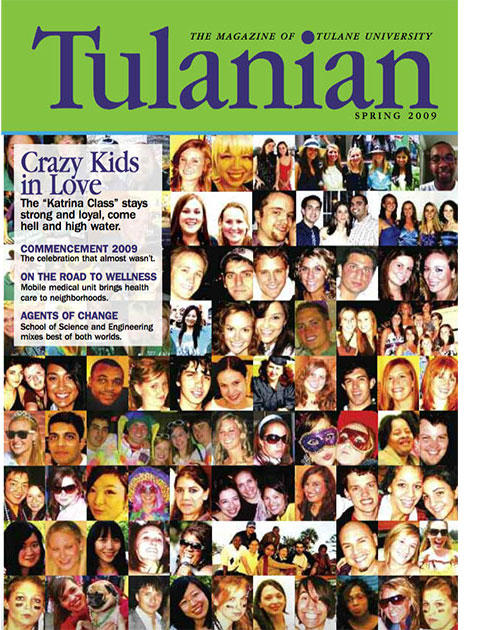

Above: Section from an afterimage photographic scroll, a work in progress

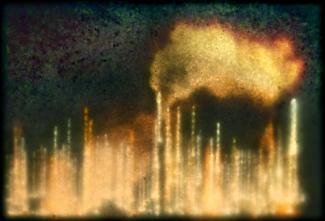

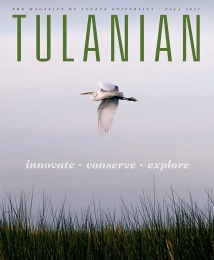

The electrified banks of the Mississippi River in southeastern Louisiana are both concrete and symbolic in the photographic work of Associate Professor AnnieLaurie Erickson.

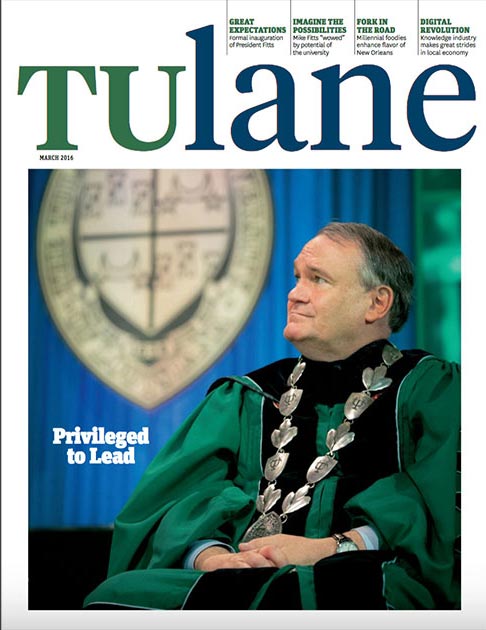

In her “Slow Light” series, white-hot energy pours off those refineries, creating a glowing landscape against the night sky. But the factories along the 85-mile stretch of the river south of Baton Rouge spotlight questions about the relationships between industry and the environment, between residents and economic development.

Erickson, an associate professor of photography and associate chair of the Newcomb Art Department in the School of Liberal Arts, arrived in Louisiana in 2012 and was immediately drawn to the landscape of refineries. She began capturing these “strange forbidden cities” and the role of the river in “Slow Light” the next year.

Now, Erickson is working on a new iteration of the series, with photographs taken from a vantage point on the Mississippi River, documenting, artistically, larger segments of the petrochemical and other industries along that stretch.

“As a photographer, I’ve always been interested in capturing things that are a part of our daily lives, but that are hard to see,” she said.

The billowing clouds of smoke above the refineries are easy to spot, but the overall environmental and public health toll may be harder to pin down. The toxic emissions from the refineries have been blamed for increased risks of cancer in the region and are the subject of study by regulatory agencies. The river itself is cleaner since the passage of the federal Clean Water Act in the 1970s but historically was a dumping ground.

“I’m using the afterimaging process to look at the fossil fuel industry to render this toxic landscape as these ghostly and unearthly vanishing cities that should be perceived as a relic of our destructive past,” Erickson said. “To me, as a conceptual artist, that meeting point between process and content made sense.”

The heart of Erickson’s work is the afterimaging technique, which she developed before coming to Tulane but which she continues to refine. She has received grants from Tulane’s New Orleans Center for the Gulf South and the School of Liberal Arts to support her artwork.