Portraits by Paula Burch-Celentano and Sally Asher

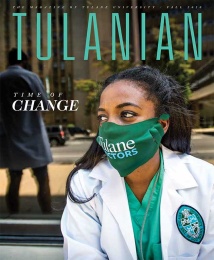

For most of us, the novel coronavirus began as a whisper. News of a deadly virus slowly seeped into our national consciousness in much the same way that SARS and MERS had several years prior — murmurings of something awful happening “over there,” an international public health crisis that we viewed more as concerned spectators than participants.

But viruses in general and SARS-CoV-2 in particular don’t care much about borders. Less than a year later, the disease that it causes, COVID-19, has taken an unimaginable toll and the lives of millions around the globe, including more than 245,000 Americans. As the world anxiously awaits a vaccine for COVID-19, we have gained a new respect for the immense power of emerging infectious diseases that can shutter schools, devastate economies, and take countless lives in just a few short months. And we have gained a new appreciation for those who spend their lives studying them, knowing that perhaps they alone can get us to the other side of the biggest public health crisis of our lifetimes.

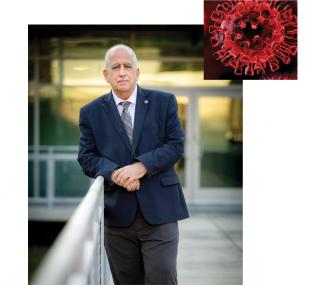

The morning after Mardi Gras, Carnival- weary employees streamed their way into the Tulane National Primate Research Center. For several weeks, things had been different. Camera crews strode around the center, mics angled toward prominent researchers who normally toil behind closed doors, immersed in their work. A few weeks prior, the center had announced that it would be among the first research institutions to receive samples of SARS-CoV-2. Now the first vials had arrived, propagated from patient zero — a Seattle man who had contracted the disease while visiting family in China. As a result, the surrounding community of Covington was on edge, wondering how the virus that was wreaking havoc across the globe could be contained within the confines of these buildings.