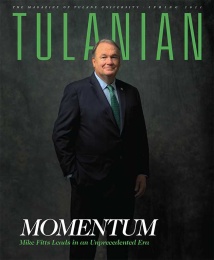

Above: Thomas LaVeist in his office at the School of Public Health. (Photos by Paula Burch-Celentano)

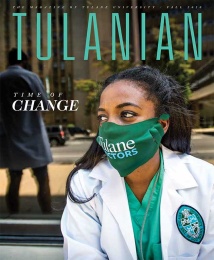

As the mysteries of the novel coronavirus unfolded during the first half of 2020, reports surfaced that the disease disproportionately affected African Americans and other people of color as compared to the overall U.S. population.

Social scientists sought to explain how inequities in health care, some rooted in decades-old racially based practices, placed people of color more at risk. Housing often contributed to COVID-19 infection rates. So did mass transportation.

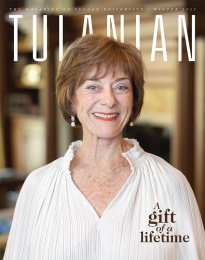

Thomas LaVeist, dean of the Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, who also serves as the Weatherhead Presidential Chair in Health Equity, emerged as a national expert whose research showed how COVID-19 affected African Americans and how years of racial discrimination could have lingering effects on health outcomes.

Like other researchers, LaVeist, a medical sociologist, recognized COVID-19’s ability to take hold in communities with a pattern of underlying conditions like diabetes and cardiovascular disease, but he was skeptical that these underlying conditions were the primary reason for race disparities in COVID-19 deaths.

LaVeist has spent more than 30 years studying disparities in health care, specifically how social and behavioral factors explain race differences in health outcomes, and what has been the impact of social policy and interventions on the health of African Americans. COVID-19 was only the most recent example of these disparities at work, even if it was the illness that got all the media attention this year. LaVeist has been featured on NBC News, ABC News, National Public Radio, and other national and international media outlets.

“Categories that determine how healthy a population is include your genetic endowment; your health behavior plays a role; then there’s what you are exposed to, what environmental risks might be where you live,” LaVeist said.

“But then there’s also the social environment — transportation being one example, or a food desert: an environment where there just isn’t access to healthy foods, or there is a great deal of community violence or your occupation. Minorities are more likely to hold jobs that they cannot do from home.” The combination of many of these factors increases minorities’ risk of contracting COVID-19.

New Orleans data supports these insights. In a city where African Americans are overrepresented in certain employment fields that place them at higher risk for COVID-19 infection, 77% of New Orleans’ overall COVID-19 deaths were in the African American or Black population as of June 5, 2020, according to the Data Center of New Orleans, working from reports provided by the Orleans Parish Coroner’s Office.

That means for all age groups 50 years or older, Black people in New Orleans are dying at a rate three to 12 times greater than for White people, the center concluded.

Body of Research

LaVeist brings to his deanship a vast body of research, experience in Congressional testimony, professional affiliations and numerous awards.

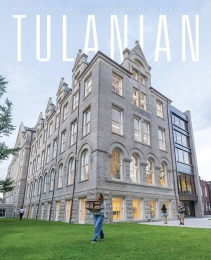

He was the first faculty member to hold one of Tulane’s endowed presidential chairs, created to support the recruitment of exceptional, internationally recognized scholars whose work transcends and bridges traditional academic disciplines. When he arrived at Tulane in July 2018 after serving on the faculties of Johns Hopkins and George Washington universities, he already knew how New Orleans fit into a snapshot of national health outcomes.

“The disparities that we see in this city are steeped in the history of this country,” he said. “In public health, in the United States, we don’t teach the history of this country sufficiently. I think many highly educated people do not know the history of the United States, especially as it relates to race and how things have come to be as they are.

“It’s easy to come [to New Orleans] and say, ‘Well, what I see is the Black people tend to be poor. And the White people tend to be better educated and more affluent.’” But without any understanding of the city’s history, the casual observer might draw the wrong conclusions about the city and its inhabitants.

“That’s a simplistic way of viewing the world, but I think that’s how the human brain operates. We try to draw conclusions from incomplete information,” LaVeist said, adding, “for some of our students” — New Orleanians — “this is their only experience they have in the United States. New Orleans is what they see.”