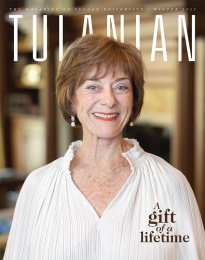

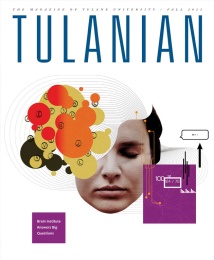

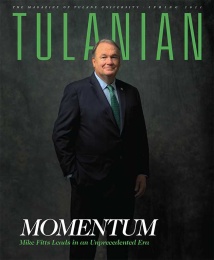

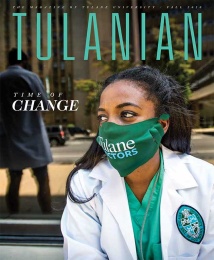

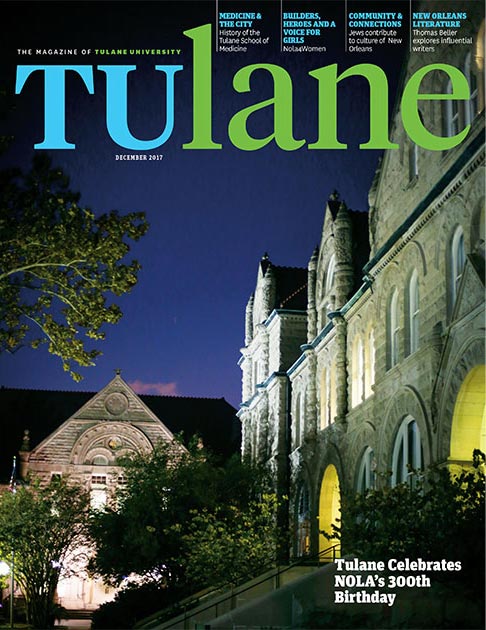

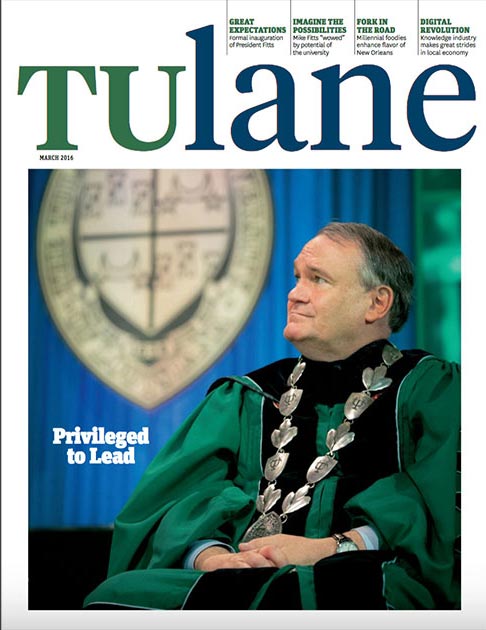

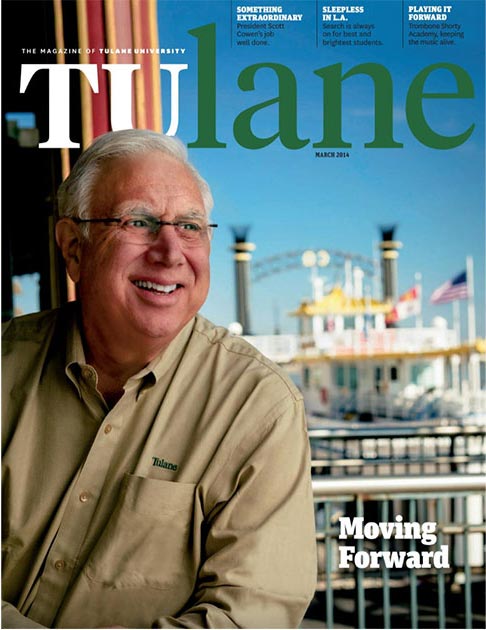

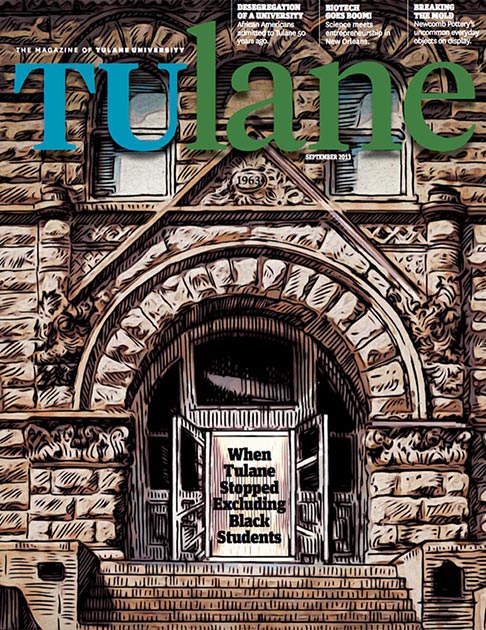

Above photo: Dr. Giovanni Piedimonte, vice president for research (by Paula Burch-Celentano)

When Dr. Giovanni Piedimonte, the new vice president of research, was asked, what is the goal of research? he said, “That’s easy: to improve the life of people.”

Everything that Tulane researchers do is focused on making “this very fragile primate (humans) have the most fulfilling, happy and healthy life possible,” he said.

Piedimonte, a distinguished pediatric pulmonologist, joined Tulane this fall from the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, where he held the Steven and Nancy Calabrese Endowed Chair for Excellence in Pediatric Care.

At the announcement of Piedimonte’s appointment to Tulane, President Mike Fitts and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost Robin Forman issued a joint statement: “Dr. Piedimonte is an internationally renowned physician, researcher and healthcare executive. He brings to Tulane a passion for impactful research of all forms, and a special interest in collaborations that bring together scholars from disparate perspectives and areas of expertise. We are confident that his appointment will ensure that Tulane, which has been responsible for world-changing discoveries and innovations in areas that range from heart surgery and infectious diseases to coastal science and Maya archaeology, will play an increasingly prominent role in expanding our understanding of the world around us and improving the lives of people around the globe.”

Piedimonte received his medical degree from the University of Rome School of Medicine in Italy, completed his residency in pediatrics at the University of California–San Francisco, and received fellowship training at the Cardiovascular Research Institute of the University of California–San Francisco and the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill. He also received training in healthcare management and managed care and capitation from the University of Miami School of Business; training in health policy and management from Harvard School of Public Health; training in healthcare finance and accounting from Baldwin Wallace University; and training in population health from Thomas Jefferson University.

Piedimonte’s research has been funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for more than 30 years and he has been principal investigator or co-investigator on more than 40 research projects. As an administrator, he’ll lead the research enterprise at Tulane, which received $137 million in funding for sponsored projects from the NIH and other external agencies in fiscal year 2018.

Piedimonte will also continue his own NIH-funded research at Tulane. His research has investigated respiratory infections, particularly in children. Lately, however, he’s looking into the developmental origins of health and disease by studying the effects of a mother’s illness, nutrition, environment and emotional state on the baby while in the womb — and after the child is born.

“More and more, we understand that almost anything that a mother experiences, in one way or another, is going to affect the fetus,” said Piedimonte. “A lot of our fate, medically speaking, but not only medically speaking, is determined before we are born.”

Piedimonte is pleased to bring his investigations that involve biomedical engineering, environmental studies and infectious disease research, as well as medicine, to the interdisciplinary setting at Tulane.

He’d like other Tulane researchers to know: “I am one of them.”