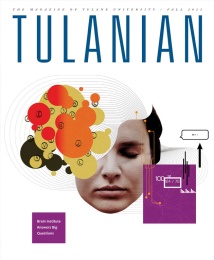

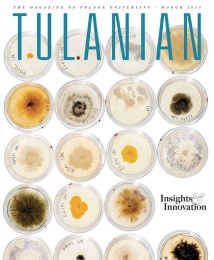

In her cross-disciplinary Behavioral and Neurodevelopmental Genetics Laboratory, Dr. Stacy Drury and her colleagues study the relationship between childhood experiences and genetic and epigenetic factors, striving to understand how this shapes a child’s long-term development and health.

Epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression that are caused by factors that are “above” the genome or the DNA sequence. Epigenetic markers, in response to environmental events, influence how much, when and where genes are turned “on” or expressed in different tissues and parts of the body.

Drury’s research shows that adversity early in life — exposure to community or family violence, family instability and early institutional care — influences specific epigenetic factors and may offer new clues into how an individual develops behaviorally.

The School of Medicine, with its close relationships and partnerships across the university, affords Drury an enviable setting for her research initiatives.

“We can integrate genetics and neuroscience and developmental psychology,” said Drury, the Remigio Gonzalez, MD, Endowed Professor of Child Psychiatry, an associate professor of psychiatry, and the vice chair of research in the Department of Pediatrics, “and at that interface we can learn about mechanisms in a way you can’t do in a separate field.”

The broad term “early experiences” that lies at the root of her research envelops trauma and adversity, the same situations of violence and poverty that plague New Orleans communities. Drury’s studies show that traumatic and stressful experiences in childhood — disruptions in home life and a constant diet of seeing or even enduring violence, ongoing poverty and natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina may alter the very DNA sitting on the tips of chromosomes. Moreover, the impact of traumatic experiences appears to cross generational lines, raising the risk of chronic conditions and diseases later in life.

People, particularly children who have been exposed to high levels of community violence, not only have higher levels of “externalizing behaviors” such as aggression or oppositional behavior, but also show changes in their biological markers of stress, including differences in the endocrine and cellular stress pathways. The pathways are linked to later mental illness and also contribute to obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes — all public health threats that are to some degree preventable.

“These same stress-response systems that are relevant for socioemotional function and behavior and mental illness underlie [biological] health outcomes as well,” Drury said. “Rates of obesity are directly related to child maltreatment history. Increased rates of cardiovascular disease are seen in people who have been exposed to violence.”