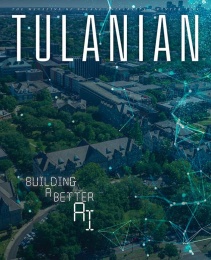

Stronger Community Connections

In April, the center held a workshop for academics and community partners to discuss emerging issues in AI and to identify risks on the horizon as AI’s impact continues to grow. While many of the researchers had existing relationships with some of the groups, the workshop enabled them to strengthen those connections and make new ones.

“We now have several strong partnerships that will serve as the basis for research and proposals in year two,” Culotta said. “Additionally, we plan to create a Community Advisory Board to provide more regular interaction with project partners.”

Researchers teamed up with groups such as Court Watch NOLA, Eye on Surveillance and the city of New Orleans to study AI’s impact on their work and society in general.

Boyles and Culotta are working with a nonprofit group called Eye on Surveillance to better understand the use of government surveillance tools such as facial recognition and whether the tools have an impact on crime.

Boyles said the software illustrates how AI can lead to the expansion of racialized surveillance, stigmatization and criminalization, often unbeknown by and to the detriment of Black people and other marginalized groups. “We need to further understand and counter everyday harms that may be exacerbated through computer technology,” she said.

Culotta is also working with Court Watch NOLA, a nonprofit group that trains volunteers to monitor and report on the efficiency of the New Orleans criminal justice system. Together with computer science seniors as part of their Capstone Service Learning course, they built a transparency dashboard to better monitor effectiveness and equity in New Orleans Magistrate Court. Culotta and Boyles are using that work to seek National Science Foundation funding for developing additional community-driven tools to monitor the New Orleans criminal court system.

Button, executive director of Tulane’s new Connolly Alexander Institute for Data Science, is conducting research that seeks to use AI to detect discrimination, specifically as it relates to access to therapy appointments.

“I’m doing an audit field experiment, a sort of ‘secret shopper’ study, where therapists get appointment request emails from prospective therapy patients,” Button said. “The requests are, on average, identical but from individuals with different names, which varies the perceived race, ethnicity and gender of the patient.”

He is using an AI tool called natural language processing (NLP) to detect potential subtle discrimination in how therapists respond to appointment requests by email based on the patient’s name.

“NLP can help determine, for example, if therapists send less helpful or polite emails to Black or Hispanic prospective patients,” Button said.

Bazzano is investigating new methodologies for community-driven AI, borrowing from public health, which has a rich history of community-engaged research.

“Artificial intelligence is a technical and social innovation with great potential to positively impact public health, for example, enhancing disease prevention and detection, accelerating behavior change and enriching approaches to improving health,” Bazzano said.

“However, there are also potential harms of applying AI in public health, which must be addressed to allow this innovation to have a net positive impact. We seek to interrogate and carefully consider these potential harms and to identify community-engaged solutions to fully realize the potential benefits of AI as a social innovation.”

They include appropriate safeguards to protect patient data and privacy when using AI in health and consideration of the real and perceived risks of privacy violations. “The use of sensitive health data and access to it by unknown individuals or organizations is a major concern for AI and other sociotechnical innovations,” Bazzano said.