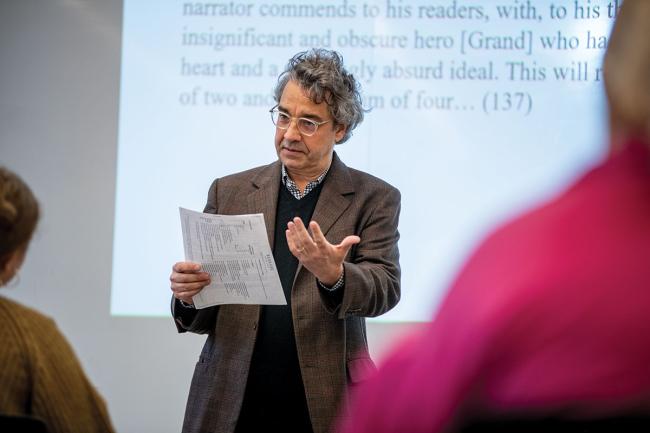

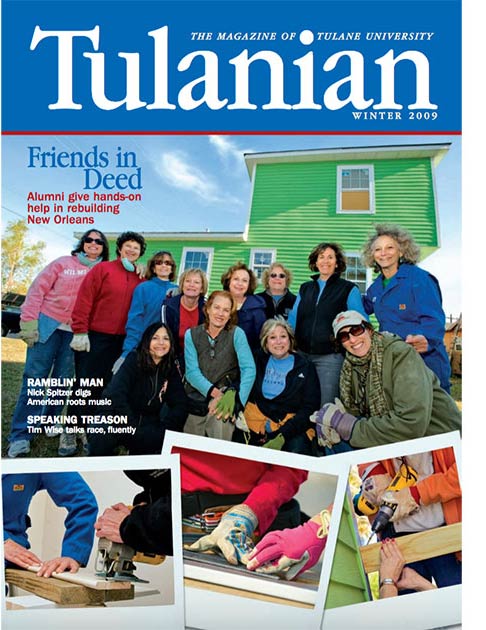

Above: Thomas Albrecht teaches a seminar about literature of plagues for the third time since the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020. (Photos by Paula Burch-Celentano)

The idea of a course called Writing About the Plague came to me sometime in spring 2020, during the very early weeks of COVID. These were the weeks of being locked down in our homes. The days of wiping down mail and packages, of “Stay home, New Orleans!” public service announcements, of banners thanking essential workers. Tulane had moved to all-virtual instruction for the remainder of the spring semester, and my 7-year-old daughter was completing first grade on a laptop computer.

My initial idea was to spend some of my time in lockdown reading or rereading what certain writers I love, writers in whose writings I have sometimes found wisdom, had written about plagues and living in times of plague. Plagues have been part of human experience since the earliest days of writing. They play important roles in Homer’s Iliad (written down around 700 B.C.E.), the Biblical Book of Exodus (written down between 600 and 400 B.C.E.), and Sophocles’ Oedipus the King (first performed around 429 B.C.E.).

My subsequent idea was that if reading what these writers had written about plagues was proving meaningful to me, was helping me make sense of an uncertain and scary time, it might prove meaningful and helpful to my students as well. I remembered the frightened, befuddled expressions on my students’ faces in our final in-person class meetings in March, just before we were all sent home. I knew I was scheduled to teach a senior special topics seminar in the Department of English in the fall, though like everyone else at the time I had no idea what the fall 2020 semester at Tulane would be like. I contacted my department’s Director of Undergraduate Studies and asked her to change my fall course topic to Writing About the Plague.

I spent the summer of 2020 a bit like the young protagonists of Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron, who escape the 1348 “Black Death” bubonic plague in Florence by isolating themselves in a countryside Palazzo and pass the days telling themselves stories that are full of life. My family left New Orleans, we rented a house in rural New England, barely saw anyone, and I spent my time reading writings about plague. This reading was for me an antidote to COVID and worrying about COVID, much like the wonderful, vibrant stories in The Decameron were an antidote to the Black Death for the young people telling and hearing them.