“How’s Ya Momma N’ Dem?”

Pre-pandemic, Dajko and Carmichael recruited participants any way they could: at festivals, at the store, at cultural centers and other venues where they could easily interact with community members.

Early analyses show that some of the traditional features of the New Orleans dialect are on the decline in everyday speech.

“Some of those iconic features that, for example, you can see on T-shirts in the city: ‘makin’ groceries,’ ‘How’s ya momma n’ dem?’ and other pronunciations as well, are starting to be used less and less,” Carmichael said.

The term often used to describe these features is “Yat,” a label for the White-working class accent that sounds to many like a Brooklyn, New York, accent.

An example of this can be heard in the word “darling.” Someone with a Yat accent pronounces the word “daw-lin,” essentially dropping the “r.” Linguists call this pronunciation non-rhoticity, or r-lessness.

Dajko said that from hourlong interviews with participants, she can generate hundreds, if not thousands, of contexts in which the “r” might be dropped. To hear these features, Carmichael and Dajko audio record interviews.Participants are asked about their lives and about living in the city. The researchers will also ask participants to read a passage with a targeted list of words and to take a survey about phrases and words they may use.

Some examples of targeted words and phrases are “Neutral ground” and “banquette” and “Does the store open for 8 o’clock or at 8 o’clock?”

Carmichael said that many younger participants don’t seem to speak with traditional “Yat” features.

It’s a normal process for some speech features to be used less over time, since language is always changing. Interestingly, in New Orleans the change may be happening at an accelerated rate.

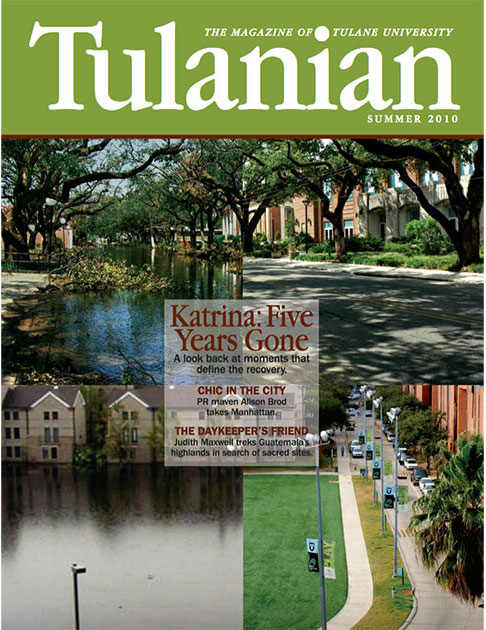

One of the main possible factors for this accelerated rate is, of course, Hurricane Katrina, although it is not a sole catalyst, the researchers said.

“In our data, we see that the change was already in progress before Katrina, so people already were starting to shift away from these linguistic features,” Carmichael said.

Another possibility is that individuals became more aware of the language features while they were displaced because of the storm.

“We have a lot of stories of people saying things like, ‘I never knew I had an accent until the storm.’ ‘I never realized I talked a specific way until I came in contact with somebody who pointed it out to me,’” Carmichael said.

Carmichael said that some New Orleanians may have become more aware of how they speak because of others’ judgments, sometimes negative, when their accent was heard.

“‘Well, I don’t want someone to think that way about me. I don’t want someone to listen harder to how I say something than what I’m saying.’ That’s what one of our participants said.”

Creole No More

In one task used to assess local perceptions about the distribution of certain accents across the city, participants are asked to circle areas on a map of the city where they think people have accents. There is much agreement that people in Chalmette have an accent, said Carmichael, as well as consensus that people Uptown talk “fancy.”

Often perceptions correspond to social factors.

“People will say things about how different neighborhoods speak differently from each other, and when you look up the demographics of those neighborhoods, you see they’re stratified according to social class or according to ethnicity,” Carmichael said.

To take a (recently famous) example, the speech of Metairie, Louisiana, native Amy Coney Barrett was challenged by listeners during her confirmation hearing for appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court. One New York podcaster asked on social media, “Why does Amy Coney Barrett have a faint, low-key Long Island accent?”

Since many traditional New Orleans English features are shared with the English spoken in New York City, it is perhaps unsurprising that those unfamiliar with the way New Orleanians speak would accuse Coney Barrett of affecting a “Long Island accent.” But as Carmichael and Dajko pointed out, social factors may intersect to play a role here.

Carmichael did not detect any specific features in Coney Barrett’s way of speaking when she listened to recordings of the confirmation hearing. “She’s White. She’s suburban. We know from our previous work that these factors can predict retention of traditional ‘New Yorky’ sounding features within Greater New Orleans. So it’s likely that this is what listeners are keying into, even if I am not hearing it.”

Dajko added, “She’s well-educated, so in most contexts in which we’re going to find her recorded, we’re going to hear something very standard.” That is, in more formal contexts speakers may minimize their use of nonstandard linguistic features, meaning that Coney Barrett’s use of local features could be quite subtle. What listeners might be tuning in to, Dajko noted, would require extensive analysis, but it’s just this kind of thing that the researchers are hoping to learn from the project.

Part of the researchers’ data collection process is that participants are asked to identify themselves ethnically. Participants in the study have primarily identified themselves with either White or Black ethnic groups, and results are showing that some aspects of their speech vary among the two groups.

“If you think about the communities that people interact with, and the individuals who are talking to each other, this may not be that surprising that you’re going to find a difference,” Carmichael said.

The Creole ethnic group that is specific to South Louisiana is of special interest to the researchers.

While the term has many definitions, Creole is often defined as someone who is multiracial, especially people who have French, Indigenous, African, Spanish, Portuguese or other diverse backgrounds in their family history. The descendants of free people of color in New Orleans have also been defined historically as Creole.