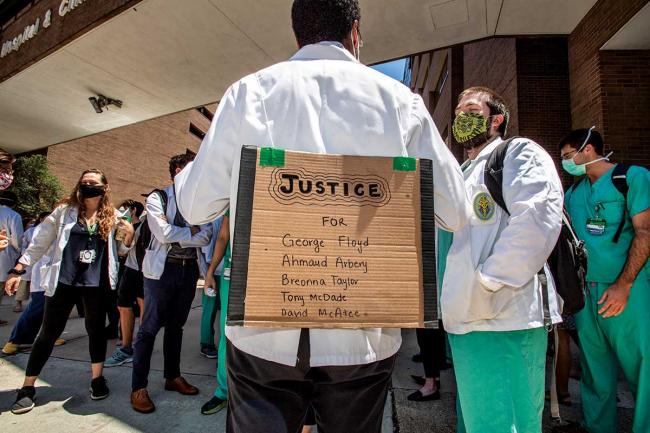

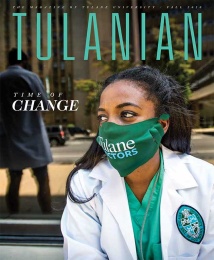

As part of Tulane’s endeavor to be “actively antiracist,” Singh is in the process of looking at the university’s policies, practices and procedures where there are inequitable racial outcomes.

“One of the most important things in making Tulane a more welcoming place for students of color is engaging conversations about racism with White folks on campus — White students, White faculty, White staff, White administrators. I think students of color, faculty of color, staff of color are usually pretty used to thinking about racism a lot.”

These conversations about racism begin with the question, what is race? What does it mean to be White? What does it mean to be Black, Indigenous or another Person of Color (BIPOC)? Is the “White” way always the right way?

“The goal of an education at Tulane is being prepared to engage in some of the most courageous and challenging conversations of our time about race and racism,” said Singh. “We know if racism exists in the world, then there will be racism at Tulane. If we acknowledge that reality for BIPOC community members, then we can get less afraid of making mistakes in discussing racism and get busy changing our policies, practices and procedures. We can become more vigilant and determined about developing antiracist practices and engage in conversations about race and racism more boldly, with innovation, compassion and patience — but also determination to make social change.”

Hip-Hop Lived Experience

From her experience as an undergraduate (she earned a Bachelor of Arts in 1994 and returned to the university as an English department faculty member after earning a PhD from the University of Illinois), Nghana Lewis thinks Tulane has done a good job of providing safe spaces “in which students feel comfortable expressing themselves and sharing their experiences in an unfiltered way.”

An associate professor now, Lewis has been teaching at Tulane since 2005. Every year, she feels, “I’ve got the most brilliant students in the world.”

The level of “wokeness” in students in the past five to seven years is “extraordinary,” said Lewis. “They are bold. They are bright. They are thinkers. They are doers.”

Faculty can learn from their students, said Lewis, if they listen to them.

“We are charged to teach and educate and expand their horizons. But there’s so much they can teach us, from what they’ve lived and what they’ve experienced and what they’re doing. And that’s across the board: Black, White, Hispanic. They’re coming in with a level of knowledge and know-how — knowing how to do things, knowing how to organize — that’s inspiring.”

Faculty have to continue to push students to be constructively critical in analysis of the dynamics of inequity at all levels — institutional, social, cultural, personal, said Lewis. These inequities have an impact on “people’s lived experiences in material ways.”

“Woke” is imported from hip-hop language, an art form that Lewis has extensively studied. As a native Louisianian from Lafayette, Lewis said that hip-hop is her “lived experience.” She’s also explored White Southern women writers. In her book, Entitled to the Pedestal: Place, Race and Progress in White Southern Women’s Writing, 1920–45, she argues that these writers are not “monoliths,” but they “wield power and influence” from their positions of esteem in White society.

Lewis’ current focus of research is the HIV-AIDS epidemic and its impact on Black women.

When asked by a White colleague shortly after the George Floyd murder, “What can we do?” in response to the Black Lives Matter movement, Lewis said, “You can educate yourself.”