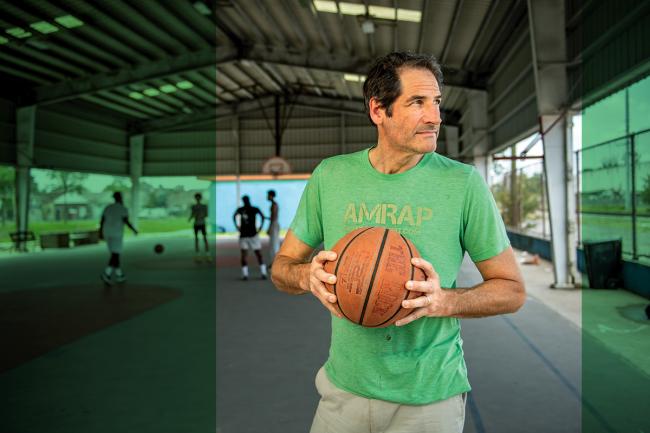

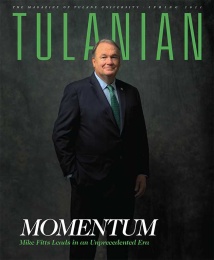

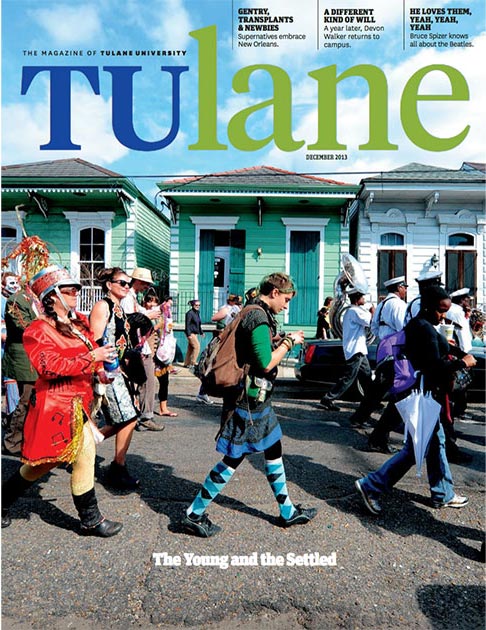

Above: Thomas Beller’s got game and is ready to play on the rain-proof court at Leake Avenue and Prytania Street. (Photography by Paula Burch-Celentano)

The Maserati Kid

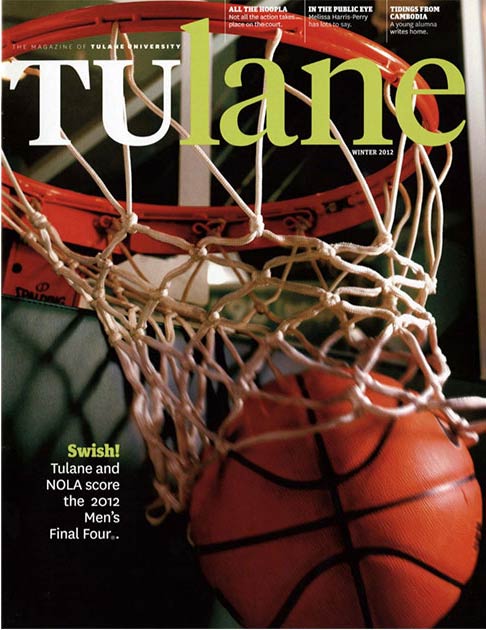

I turned down the driveway, which descended slightly from the road, the house barely visible through the pines. The feeling was of entering a secret world. Just past the open-air garage, filled with vintage Corvettes and Maseratis, was a basketball court.

It was a sunny August morning in East Hampton. I had come to play in a memorial game for a man who had died in the Twin Towers. The man who had built this house.

I was a friend of a friend, recruited to help fill out the roster. Since the guy’s last name started with g, and since my childhood friend Jimmy Gartenberg was killed on that same day, in that same place, I gave a private nod to Jimmy.

The basketball court was a fantasy: glass backboards, three-point lines, beautiful landscaping. A TV crew would be filming, I had been told. The widow had written a book. I would be both participant and prop.

The game got going, grown men hustling. The players were mostly members of my tribe — middle-aged guys who seem normal enough until you see them on a basketball court, satisfying the need.

A boy played too — fourteen or so, braces, spindly arms. It was the boy’s father who died on 9/11. He was hitting shots like crazy. Game of his life. At first I thought this was touching. But then I began to feel irritated that everyone was giving him room. There is an entitlement to pulling up for a long jump shot.

A woman mingled on the sideline amid the men. She was well put together, in jeans and a white blouse, hands in her back pockets. The widow. A photographer stood on the sidelines, snapping shots with a telephoto. What was so far away, I wondered, that she needed that zoom lens?

The kid was hustling, driving, taking shots, and making most of them. Voices of encouragement and praise came from the sideline.

Someone told a story about standing on this court with the widow just after 9/11. “I’ve got this asphalt jungle back here,” she said. “What am I going to do with it?” Just then her boy, four years old at the time, came out and started dribbling a basketball.

Apparently his dad had been really good. But a dead baller is like the fish that got away, always much better in memory. I looked at the kid now, wheeling and dealing. I was moved, happy to see him so supported by his dead dad’s friends. But supported in the context of such outrageous wealth is a complicated word.

The next game, I waited for the kid to drive the lane. I was going to block that kid’s shot, smack it over the gorgeous landscaping, show him what happens in the real world. But his dad died on 9/11. Isn’t that knowledge enough?

At any rate, I never got the chance. The teams were changed. Now he was on my team. I watched him hoist jumpers. Score.

In the end, after the last game, I slapped the kid five, said, “Good game.” I shook the widow’s hand.

Leaving, I paused at the garage, its floor polished as glass. The Corvette was a shimmering silver. I wonder, now, Why did I wipe my feet?

—2011

Excerpt from Lost in the Game: A Book About Basketball, reprinted with permission. Copyright Duke University Press, 2022.