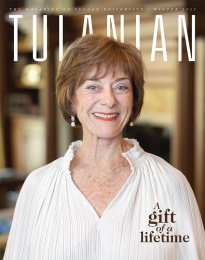

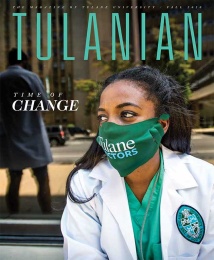

Above photo: Liz Davey, director of the Office of Sustainability (Photo by Paula Burch-Celentano)

“I just love seeing people out riding their bikes. It’s so many more people than ever before riding their bikes, and [now we have] better accommodations for bicyclists,” said Liz Davey, director of Tulane’s Office of Sustainability.

Throughout Davey’s two decades at Tulane, she has contributed to many “wonderfully successful” projects involving students, including the New Orleans regional bicycle master plan for which her office was awarded a grant in the early 2000s.

“Our students were involved from the ground up,” said Davey.

That a number of Tulane alumni, as city employees and advocates, are still involved with maintaining and expanding the city’s bicycle infrastructure is “so rewarding,” she said.

The word rewarding can easily describe Davey’s 20-year career as director in the sustainability office. She has been an innovator in making the Tulane campus more sustainable and environmentally conscious, serving as a resource to campus partners, usually students, to push Tulane toward becoming a model green university.

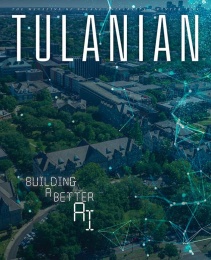

In 2015, Tulane adopted a Climate Action Plan that Davey is working to implement. This road map includes ways in which the university can reduce its environmental impact in its daily operations. There is a short-term goal of reducing the campus’s greenhouse gas emissions by 15% by the end of 2020 and a long-term goal of reaching carbon neutrality by 2050.

“In addressing climate change, our energy use is our biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions, so we want to shrink that as much as possible and eliminate the dumb waste of energy,” Davey said. “I often say, if people could somehow see the wasted energy in the same way that we can see trash, people would be much more outraged about it.”

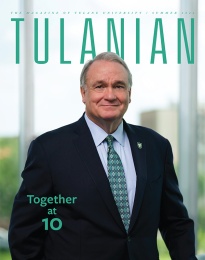

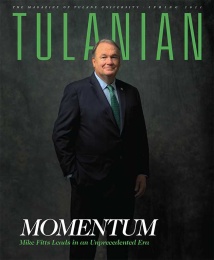

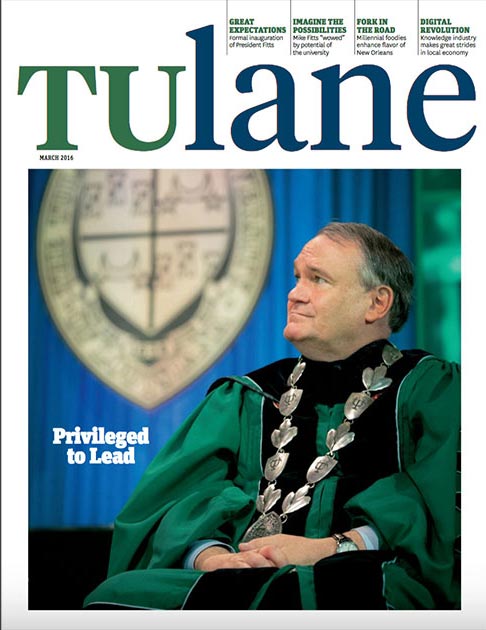

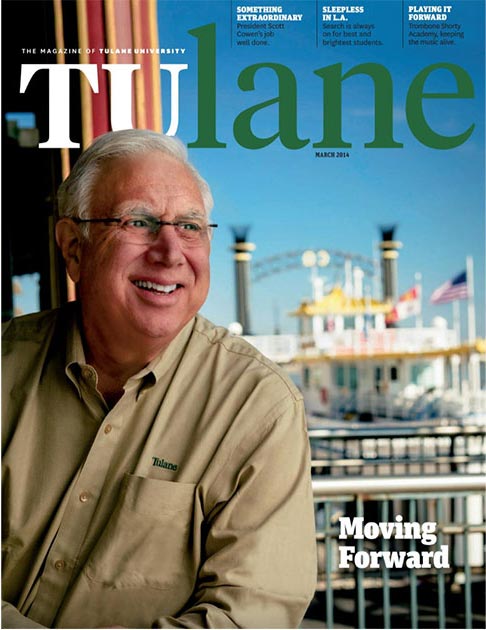

Tulane President Mike Fitts enthusiastically backs the Climate Action Plan. During his State of the University address on Sept. 6, he announced that the university is on track to meet the short-term goal and remains committed to the long-term goal. Tulane is also continuing to ensure that new buildings are constructed to receive Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification — the U.S. Green Building Council standard for green building design and operations.

“One of the top priorities of my administration is reducing the environmental impact of our operations and supporting sustainability efforts across the Tulane community,” Fitts said.