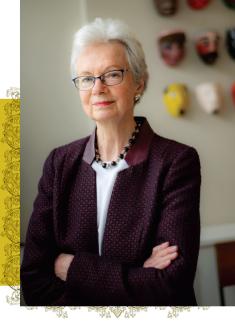

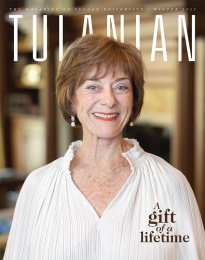

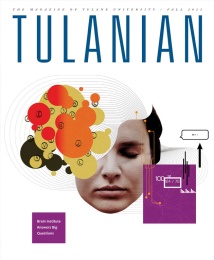

Elizabeth Boone

Elizabeth Boone, professor emerita of art history at the School of Liberal Arts, originally came to Tulane seeking a professional challenge. After 15 years as the director of the Pre-Columbian Program at the Dumbarton Oaks Museum in Washington, D.C., Boone said she wanted to pursue work related to 16th-century Mexico and thought that an academic position would facilitate that mission.

“I wanted to advance my own personal intellectual interests, which included the interaction between the Americas and Europe following the Spanish conquest, and larger issues related to graphic communication,” Boone said. “A university is a vast collection of professors, researchers, staff and students from many disciplines and with very different perspectives and interests. The very diversity of a university cultivates cross-disciplinary work and innovative thinking.”

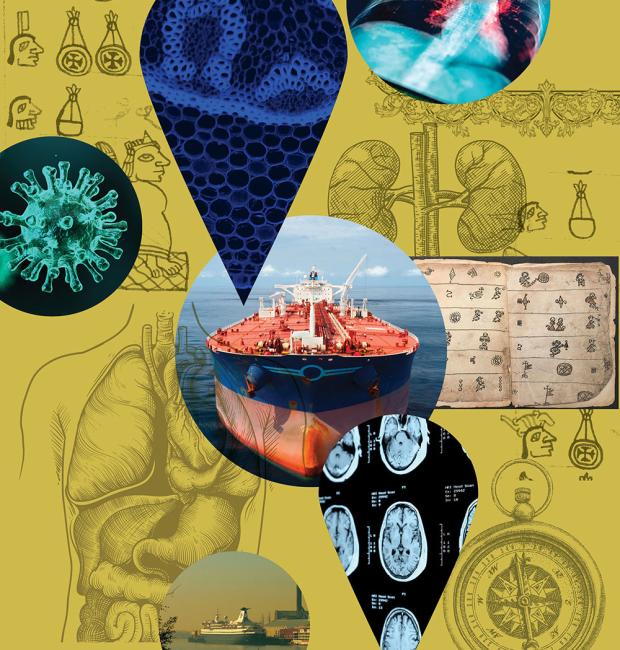

Since then, she has become one of the foremost scholars of painted books in Aztec Mexico, which include not only historical and scientific manuscripts but civil documents like court and census records.

“At Tulane I have been able to develop a series of books that together provide a comprehensive, in-depth analysis of the Mexican tradition of pictographic writing and painted books, books of native paper or hide that were created and used before and after the conquest. These include books of history, philosophy, science and divination. Too, I have been able to show how, for indigenous Americans, art largely serves to communicate knowledge the way we think writing does, and that for indigenous Americans, the reverse is also true: Writing is art.”

When she arrived at Tulane in 1995, Pre-Columbian art was still developing as a disciplinary focus.

“Pre-Columbian art history challenged traditional art historical approaches by asking us to think about an art that functioned as both art and writing, was largely anonymous, and was a significant actor in the fabric of society,” Boone said. “This caused the discipline of art history to rethink its definition of art and to consider visual culture more broadly as means to communicate ideas.”

In her years at Tulane, Boone served as the Martha and Donald Robertson Chair in Latin American Art. Now, as art historians begin to examine cross-cultural influences in all periods of the art world, Boone’s work is evolving accordingly.

The intersection of writing and art “leads to larger questions about how humans throughout time and in different places recorded knowledge without ‘alphabetic writing.’”