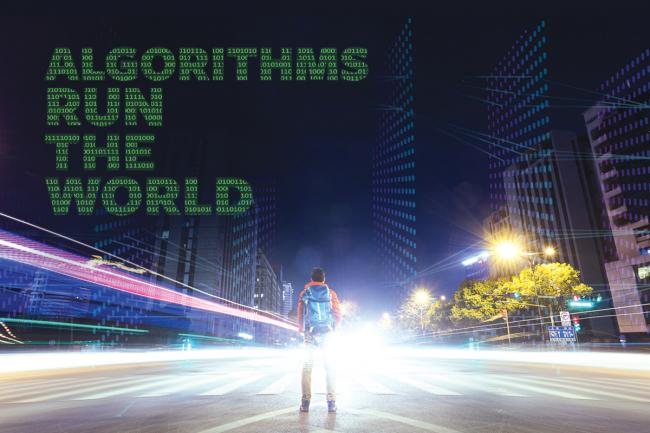

Ethical Issues in AI

Access to data is “arguably what computer science people have wanted since the beginning,” said Nicholas Mattei, assistant professor of computer science, “because data is the thing that drives how we build and test these systems.”

Mattei teaches data science and artificial intelligence at Tulane. He earned his PhD in computer science from the University of Kentucky in 2012.

Systems are built, using data, to predict human behavior, whether it’s what a person will want to watch next on Netflix or purchase from Amazon, or how they will act in more complicated ways.

“The way we collect all this data now is so easy and almost transparent to most people,” said Mattei. “Technology intermediates many, many things we do.”

For example, Google Maps can conveniently alert drivers to congestion on the road ahead. That’s possible because other drivers have given up data about slowdowns they are encountering when they are connected to Google Maps, too.

“We all sort of gain,” said Mattei. But “sometimes, I think a big problem is that people are giving up their data in ways they’re not sure of. We have trouble understanding the scope of data collected and how that data can be used.”

Mattei is writing a book, Understanding Technology Ethics Through Science Fiction, under contract with MIT Press, with four co-authors. It’s about technology’s impact on our lives.

“A lot of the impacts that people talk about as being AI or computer science are a confluence of many different advances in multiple fields of technology,” he said.

The goal of the book, which is geared toward computer science students and others interested in broader technology issues, is to get readers “to think about these things — not in prescriptive terms but to give them the tools and language of ethical theory and descriptive ethics.”

Topics addressed in the book are technology’s “ramifications for privacy and how we look at interpersonal relationships and knowledge.”

The notion of legal privacy as “information about you” to be protected is relatively new in human history, said Mattei.

It came about in the early 1900s after new technologies, such as the phonograph, microphone and telephone, were invented and came into widespread use. These advances allowed people to be recorded and for those recordings to be moved and reproduced without their knowledge.

Mattei’s book will offer essays by computer scientists and religious studies and ethics scholars. To spice up the book, science fiction stories also will be included.

One story is “Here-And-Now” by Ken Liu. It explores privacy issues as a young man navigating the gig economy inadvertently discovers information about his parents’ marriage when he connects with a work-for-hire app to earn extra money. Stories like this add to the conversation about the influence of technology on society.

“There’s lots of room for creativity in computer science,” said Mattei. And computer science is a place with great opportunity for new graduates.