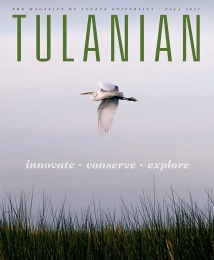

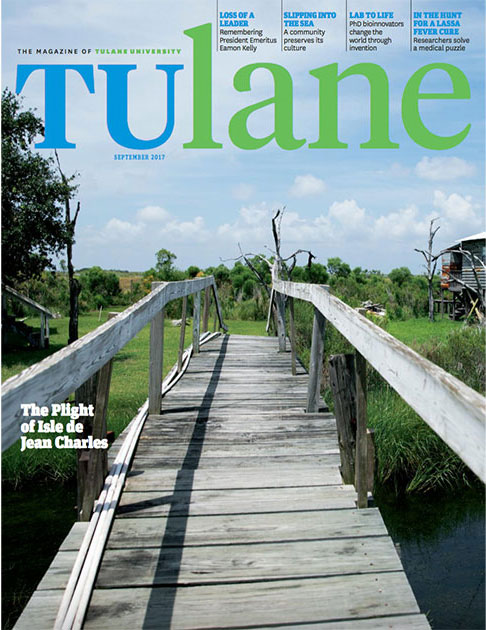

Lynda Benglis was born in Lake Charles, Louisiana. As a child, she traveled the bayous, waterways and channels that led to the Gulf of Mexico. “I preferred being on the water,” she said. She liked thinking about nature. She’d make little boats from sticks, mossy forms and leaves.

“All artists are in a kind of situation that patterns their early memories,” she said.

Waves always intrigued her—“little Gulf waves because that’s the first that I saw.”

A 1964 graduate of Newcomb College, Benglis was a student of artist Ida Kohlmeyer (NC ’33, G ’56).

Benglis moved beyond New Orleans to become an internationally known artist—and the first truly feminist artist.

Radical Sculptor

An iconic and iconoclastic feminist, Benglis took aim at the male-dominated art establishment of the 1970s. Not only did she flip the notion that so-called “feminine” values included passivity, modesty and gentility, she positively asserted her sexual and cultural power, and pushed for gender equality in the art world.

“I’ve realized that what we’ve learned to do is repress our titillations or our feelings about what we see, and we call it taste,” explained Benglis. “What is the way we see, what do we respond to, without creating a taste that’s agreeable to everyone? I’m not trying to satisfy anyone.”

Considered a radical, she pushed the boundaries of traditional art-making materials. Forsaking canvas when she poured gallons of latex paint directly on the floor of a New York gallery to create Self-portrait in 1970, Benglis was a stark contrast to the fashionable art of the day. By pouring effervescent industrial foam material used in insulation over chicken-wire molds, she produced what looked like lava flows. This process led her to the stunningly layered wave effect seen in the avant-garde sculpture/fountain The Wave of the World (1983–84).

“In color, form and content, her art was a major departure from the dominant trend towards minimalism at the time,” said Katie Pfohl, curator of modern and contemporary art at the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA). “At a moment in the art world in which many male artists were working a very restrained palette of black and white, and with very geometric minimalist form, her large pours in hot pink, electric yellow and royal blue were shocking. Lynda really did fly in the face of traditions both as a female artist entering the male-dominated world of large-scale sculpture, casting and welding, and as an artist who wholly embraced sexuality and the body. I would consider Lynda Benglis one of the best-known female sculptors of her generation.”