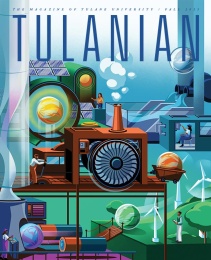

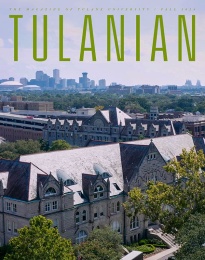

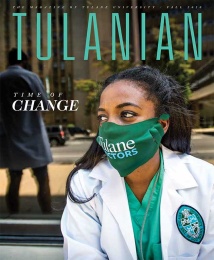

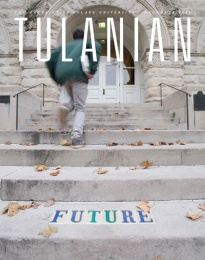

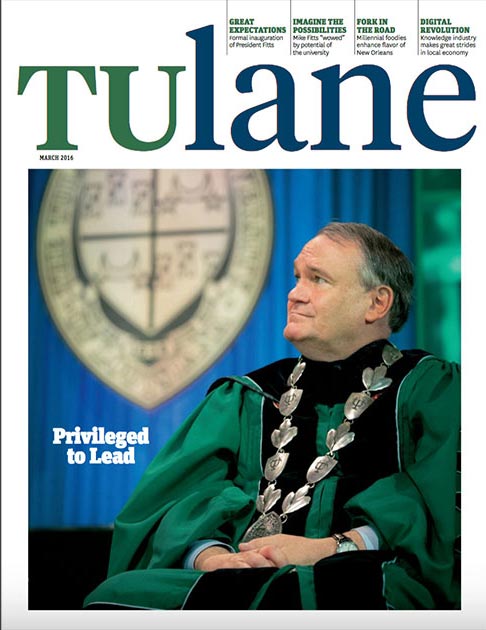

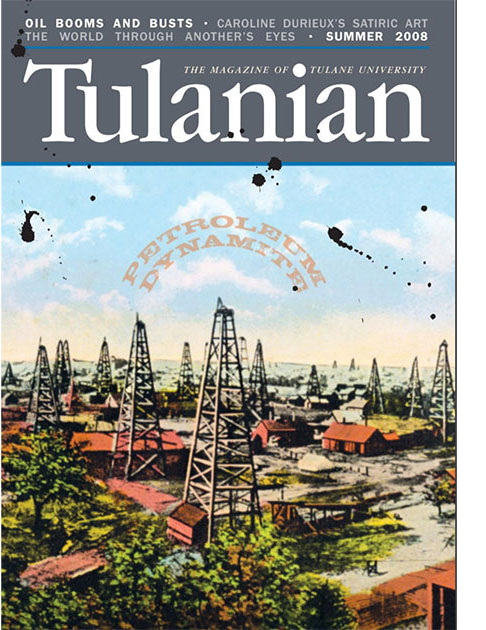

Above: Dr. Michael White, the “narrative soul” of the documentary, plays at the funeral of jazz musician Milford Dolliole in 1994. White is with other members of The Young Tuxedo Brass Band in front of St. Augustine Church on Gov. Nicholls Street. Clarinetist White estimates that he has played in more than 200 jazz funerals. (Photo by Daniel Meyer. Hogan Archive Photography Collection, Tulane University Special Collections )

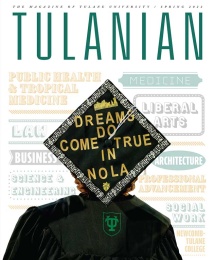

Home Movie

In an essay, journalist Gwen Thompkins writes about "City of a Million Dreams," the 2021 documentary by Jason Berry. The film traces the origins and power of New Orleans funeral parades.

City of a Million Dreams is the name of a traditional jazz song written at a time when a million of anything seemed like a lot. That was last century. Nowadays, the number sounds fairly modest, what with mega cities and mega deals and mega lottery jackpots. “What about a billion?” “A quintrillion?”

And yet, it’s worth remembering how powerful a single dream can be. It can propel human achievement in any direction to create anything, in any size, anywhere, at any time. A million is plenty. Now, the author and filmmaker Jason Berry has borrowed City of a Million Dreams as the title for his documentary about New Orleans street parades. His 2021 film and the city’s parading traditions begin with early inhabitants of the area in conversation with their ancestors. Some of them came to New Orleans by choice. Many did not. But each was standing on someone else’s dreams and carrying their own forward. There’s joy and melancholy and even pain throughout Berry’s City of a Million Dreams, not unlike the sweet nostalgia of Raymond Burke’s melody arranged for clarinet, cornet and guitar.

The documentary unfolds like the best home movie, ever. Anyone who’s shown even a glancing interest in the music and neighborhoods of New Orleans will recognize familiar faces: Father Jerome LeDoux, the Catholic priest from Tremé! Dr. Michael White [G ’79, ’83], the clarinet player from Gentilly! Masking Indian Cherice Harrison-Nelson from Bywater! Music scholar Bruce Raeburn [G ’91] from Tulane! Geri Elie was my Sunday school teacher! Is that the choreographer Monique Moss [NC ’94, SLA ’09, ’12] from Tulane? It is. And she’s DANCING!!

Massive crowds of regulars along the parade routes also high-step prominently in the film. But the old brass band leaders who appear throughout dang near steal the show — “Papa” John Joseph, Ernest “Doc” Paulin, Harold “Duke” Dejan, Milton Batiste, Anthony “Tuba Fats” Lacen, and Herman Sherman, among others. They are the brass band culture bearers, now dead, whose names still mean something in this city, connecting the present street culture to the past. Watching old footage of these men play their instruments and interact with others is like witnessing something miraculous, akin to stone statues stepping down from their pedestals to share a smoke. And yet, like any home movie, City of a Million Dreams packs the added excitement of maybe seeing yourself onscreen. It’s a natural and titillating prospect for a moviegoer. “I wait for me,” the writer, psychiatrist and philosopher Frantz Fanon once wrote. “In the interval, just before the film starts, I wait for me.”

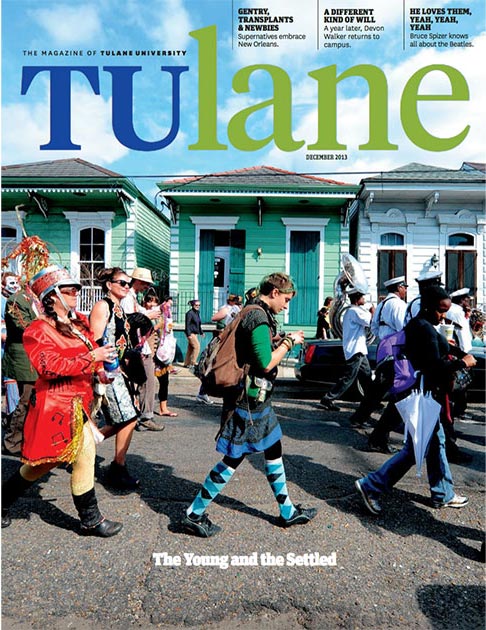

There’s a kind of unseen scrim between the local (i.e., the New Orleanian) and the outsider. On theater stages, scrims are often gossamer-like dividers that separate the action between characters, evoking two different realities in the same scene. ... Behaviors and practices that seem normal and even ordinary among locals will mystify the stranger.

Explaining New Orleans street culture to anyone is an ordeal and it’s taken Berry, his producer daughter Simonette Berry [NC ’07], executive producer Bernard Pettingill Jr. [PHTM ’73] and the seasoned editor Tim Watson years to manage it in documentary form. That’s because there’s a kind of unseen scrim between the local (i.e., the New Orleanian) and the outsider. On theater stages, scrims are often gossamer-like dividers that separate the action between characters, evoking two different realities in the same scene. I’ve bumped up against that scrim-like divide in my own work as a New Orleans–born public radio journalist. Behaviors and practices that seem normal and even ordinary among locals will mystify the stranger:

“Why do we have to spend so much time in your story on how the Mardi Gras Indians look?” an NPR culture editor once asked me.

“Have you ever seen them?” I answered, baffled.

“Do we have to call Fats Domino ‘fat’?” another asked.

“Yes.”

Using cleverly edited reenactments of African ring dancing at Congo Square, animated collage drawings, historical commentary, and music, Berry brings much-needed context to street parades so that everyone understands the city better than they did before. Some of the images are particularly affecting, as when the film depicts an 1853 yellow fever epidemic in New Orleans. So many people were dying with fever then that bodies reportedly filled some of the local music halls. In City of a Million Dreams the camera pauses over a drawing of a roomful of pleasure-seekers dancing on floorboards above the dead below. “Enjoy yourself,” the image seems to say, predating the Sigman and Magidson song. “It’s later than you think.”

For reasons relating to the city¡¯s colonial past, its geographic location, and its vital importance to the African slave trade, the scrim surrounding New Orleans is more opaque. That may be why so many people worldwide are attracted to the city. They like a mystery. In 2018, Berry published a history book, also titled City of a Million Dreams, which coincided with the New Orleans tricentennial. In the book, he lifts the scrim as best as nearly anyone can, concentrating on real-life characters who decided something, or did something, or made something centuries ago that repeats still in local tradition.

The first chapter begins in the 18th century with the French founding brothers Iberville and Bienville. They dominate any number of Indigenous people, best the Brits, break the terrain, and weather the weather to build and maintain the grid of their newly dug port city. Nowadays, the city grid the brothers worked so hard for is only a neighborhood of New Orleans — the French Quarter — and a frequent leg of street parading past and present. One of the last chapters of the book focuses on the clarinet player and Xavier University scholar Dr. Michael White, whose knowledge of his black Creole ancestors, born in the 19th century, only strengthens his resolve to make traditional New Orleans music in the 21st century. White’s trials and triumphs in the city help illustrate what it means to love New Orleans. Violent hurricanes and even more violent violence can make the loving hard.

What White and the other characters in Berry’s book learn is that New Orleans will break your heart. (Even Bienville ended his days forgotten in Louis XV’s Paris.) But, in some cases, the people in the book also learn that New Orleans can help put your heart back together again. In a fashion. Maybe. But it would be wise to keep the statins close.

In the film City of a Million Dreams, White and several of the other commentators echo remarks they made in Berry’s history book. They’ve been in conversation with him for decades, and on film we watch them grow older and probably wiser as the years pass. While White is the narrative soul of the documentary, the camera returns over and again to the cultural reporter Deborah Cotton, as well as the stout-hearted trumpet player Gregg Stafford, and Fred Johnson, the tart-tongued leader of the Black Men of Labor Social Aid and Pleasure Club. Johnson looks especially sharp on the parade route. (“This is a sway music,’ he says authoritatively. “You take your time with this. And you sashay through this.”) The saddest moments are when someone who looked so vibrant in one instant is being funeralized the next, as yet another example of how unpredictable life and death can be in the city.

And then there are André Cailloux and Pierre Casaneve, who likely started the city’s brass band funeral tradition. Each man figures in Berry’s book and film. Cailloux (pronounced: KAI-yooo) was a Black Creole cigarmaker, a former slave, and a Civil War captain in the Union Army, who died in 1863 on a battlefield upriver from New Orleans, near Port Hudson. Casaneve (pronounced: CAS uh nev) was a New Orleans undertaker inspired by Cailloux’s heroism in action. He organized a public funeral for Cailloux that was so grand it was covered by The New York Times and other out-of-state newspapers. But Casaneve, who was also Black and Creole, took the opportunity to make an unprecedented decision. He hired musicians to accompany Cailloux’s body to the cemetery. The New Orleans papers criticized brass music at a funeral procession, but the idea caught on.

Few discrete moments in New Orleans history underpin today’s funeral parade tradition as directly as the Cailloux episode. In addition to Berry, other storytellers have covered its historical precedent, most recently author Michael Tisserand in his 2016 book Krazy Kat: The Black and White World of George Herriman and author Fatima Shaik in her 2021 book Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood.

Perhaps the most compelling reason why Cailloux’s story reverberates here is because New Orleanians never tire of dying. Death is an ever-present subject of preoccupation, heartache, and professional opportunity in the city, evident in the way its residents and musicians have comported themselves lo these three hundred years. The anxiety that arises from humans living within inches of sea level — in this heat, with this water table and this insect life, with these hedonisms and hurricanes — makes the intense loyalty to the city among locals endlessly fascinating. “Why don’t you move?” my friend Susan Linnee, then of the Associated Press, asked two area women during a hurricane in the early 1970s. “Ain’t you got a home?” they replied.

The drums, the dancing and the chanting were tools of communication. “They didn’t have psychiatrists,” Fred Johnson says. “These people had to figure out how to be happy in an insane environment.”

Now, imagine what it was like for the early inhabitants of the city who hadn’t come here by choice. Those untold thousands, if not millions, were stolen from their African homelands, put on ships and brought to New Orleans to be sold into bondage. For generations of enslaved African-blooded people and free people of color living in New Orleans in the 18th and 19th centuries, death was only a gossamer-like scrim through which they could condole with their homeland ancestors on Sundays in Congo Square. The drums, the dancing and the chanting were tools of communication. “They didn’t have psychiatrists,” Fred Johnson says. “These people had to figure out how to be happy in an insane environment.”

The contributions those Africans and their descendants made to the city’s parading traditions are apparent in Berry’s film. But African-blooded people in New Orleans did more than that. Congo Square has since become known as a wellspring of American popular music. And if Johnson is correct, it all began as a kind of weekly group therapy session just outside the French Quarter.

City of a Million Dreams follows the various timelines of Africans, Indigenous people, Europeans and Americans in New Orleans and pieces together how their various tribal customs co-mingled to create a one-of-a-kind street culture. Berry, who has been filming parades for more than 30 years, has wrestled what Fred Johnson might call a “gargantuous” narrative into a tidy 90 minutes. And he’s had enormous help from a wide cast of characters who bring this story to life. They show the viewer the New Orleans that’s an unforgettable place to live and a spectacular place to die.

Gwen Thompkins is a journalist and writer in New Orleans. She’s currently working on a book based on her long-form public radio interview program “Music Inside Out,” which showcases the unusually varied musical landscape of Louisiana. She files stories for NPR Music, The Oxford American, Strangers Guide and The New Yorker online. Thompkins was a longtime senior editor of NPR’s Weekend Edition with Scott Simon and later NPR’s East Africa bureau chief. She is the New Orleans correspondent for WXPN’s World Café.

Watch City of a Million Dreams movie trailer