In the spring of 2018, shortly before starting my job as dean of the School of Liberal Arts, I was in Madrid. I walked over to Retiro Park, one of my favorite places in the city, but I found the gate locked. A simple announcement was posted: “Debido a las consequencias de las condiciones meterológicas y la urgencia de reparación e inspección del arbolado los jardines del Buen Retiro permanecerán cerrados.” In the spring of 2018, shortly before starting my job as dean of the School of Liberal Arts, I was in Madrid. I walked over to Retiro Park, one of my favorite places in the city, but I found the gate locked. A simple announcement was posted: “Debido a las consequencias de las condiciones meterológicas y la urgencia de reparación e inspección del arbolado los jardines del Buen Retiro permanecerán cerrados.”

My disappointment was intense and immediate.

To my side were two college-aged students, speaking in American-accented English. One aimed an iPhone at the sign. Curious, I glanced over at the screen. Everything looked as I saw it, except that the announcement was no longer in Spanish — the words on the sign were magically transformed into English. I gasped, and the students introduced me to Google Translate’s optical function.

For Generation Z, international travel and language learning operate in a profoundly different framework than for those educated before the digital age. New technologies have collapsed distances between continents; translation machines have erased some of the foreignness of foreign travel. Homesickness is softened by FaceTime or WhatsApp. Family, friends, and advisors are merely a Wi-Fi connection away. Fifteen years after Skype was launched and a dozen years since the first iPhone, it’s time to reframe the question of what a global education should aspire to be.

Study abroad has never been more popular. According to a 2018 report, 16% of students currently earning bachelor’s degrees in the U.S. will study outside the country during their undergraduate years. But immersion in another language is a harder sell, as if the global popularity of English and the ease of Google Translate excuses students from the difficulty of entering another system.

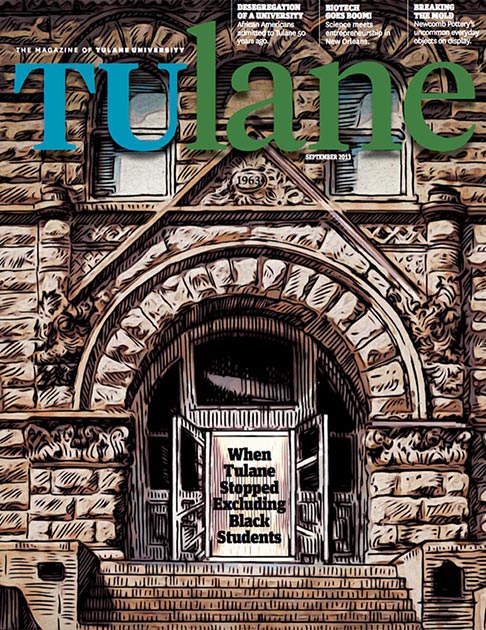

The pressures on language learning are massive. The Modern Language Association continues to report significant declines in world language enrollments across colleges. Tulane’s enrollments are still solid but in the face of machine translation, many students ask, why would one put in the hundreds — or thousands — of hours necessary to learn another language?

For most Tulane students, learning a second language was a core course in high school, though it often drops off once Tulanians satisfy our language requirement, as if the French or Spanish Advanced Placement was merely an entrance ticket. But college is the time when students who have worked years to gain proficiency can finally start to do interesting things in a second language — study German or Italian film, follow Latin American media, use French-language archives, engage with Russian peers. Or start one of the many languages we offer, from those with massive numbers of speakers like Arabic and Mandarin Chinese, to idioms of the Gulf South, including Haitian Creole and the indigenous Tunica.

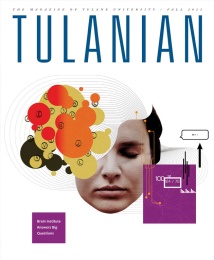

One of the traditional justifications for a liberal arts education was that it teaches you how to learn and prepares solid citizens. As we update learning objectives for the digital age, let’s specify that by embracing a second language, students gain the opportunity to think in another system. Learn how to form vocabulary from the ten forms of a trilateral Arabic root or to express yourself in Spanish’s pluperfect subjunctive or to employ politeness levels in Japanese, and you are not only building massive amounts of synapses but understanding disparate ways of life and thought, ones that no machine can translate because the differences are more instructive than the similarities.

Despite the 350 languages currently spoken in the United States (about 150 of them indigenous), a creeping monolingualism is taking over America. And even as technology appears to be screening out linguistic and cultural differences, global misunderstanding is on the rise. Tulane students, and this generation of college students generally, are socially engaged and committed to a better future. Let’s embrace ever-changing global complexity and lead boldly, even if it means getting out of our linguistic comfort zones.

Brian T. Edwards is dean of the School of Liberal Arts at Tulane. His most recent book is After the American Century (Columbia, 2016).