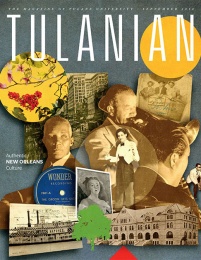

One night 10 years ago on Canal Street

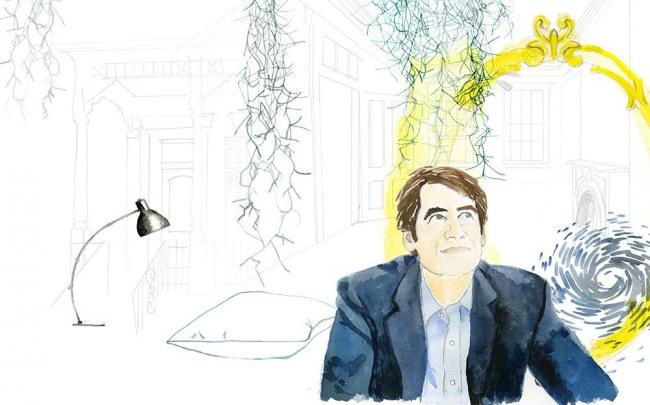

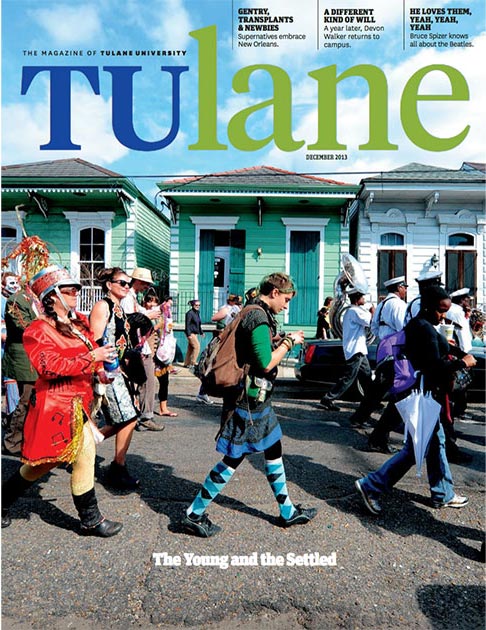

I am on Canal Street in my car late at night. Or perhaps it’s not late. But it’s dark. Even on Canal and Rampart streets, at the edge of the French Quarter, the darkness of New Orleans at night seems, to me, to be of a character and depth with which I am not familiar. I have just moved down to New Orleans from New York City to start teaching at Tulane, but I am without my wife and daughter, or any of my possessions except my car. Even the car, a used Audi A4, seems unfamiliar to me, having been driven down from New York City by a New Orleans local named Donna, with whom I shared a drink after she delivered the car. She is a French Quarter resident and tells me stories about how Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie are adjusting to their new neighborhood. Jolie had wandered into a bar the other day and sat there for a couple of hours talking to everyone, she said. Donna’s voice is wispy and melodic—I guess you could say dreamy—and seems to contain information about my new city that goes beyond the words she is saying. I think of that dreamy-sounding voice a few days later when I am on the Claiborne Avenue overpass, near the Superdome, and a car on the otherwise empty road drifts out of its lane and almost hits me. I honk the horn, feel aggrieved, but a moment later, as I pull up beside the reckless driver at the red light, I see the window lowering and a woman at the wheel. She says, “I’m sorry. I’m just so tired,” in a way that is so genuine and civilized that all the driver venom—the most insane-making kind—that I was about to deliver, mostly through a glare, but perhaps with a few words to back it up, evaporates on contact with her remark. Her voice had the same wispy, melodic, almost childish quality as Donna’s.

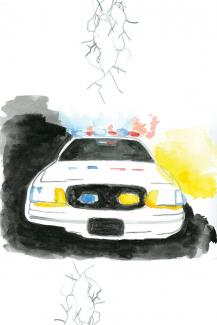

Now I am making a right on Rampart Street off Canal, there are no cars on either side or behind me, and I move slowly so I can look around. It is a dark, forlorn corner of the city. The Saenger Theatre, across the street, is shuttered and mute. Suddenly, the whole scene is lit by flashing blue lights. I look in the rearview mirror, see the police car and pull over to let it pass. To my amazement, it pulls in behind me. I wonder if it is possible to get a ticket for driving too slowly.

The officer is a burly African-American who explains that I had made a right turn from the center lane. I tell him I hadn’t realized this and offer that I just moved here to teach at Tulane and still don’t know my way around—lobbying as much as possible, in other words, to be given a break on the ticket.

“What do you do at Tulane?” he asks.

“I’m a professor,” I say.

“What do you teach?”

“Creative writing.”

“Interesting.”

“It is?” “Yeah.”

“Why?”

“Because I’ve been working on a novel.”

“Really? What’s it about?”

“Hard to say.”

“Do you have a character?” I ask.

“I don’t really have a character,” he says, “but I have a voice.”

I am suddenly very interested in this guy. I want to know about the voice. In the ensuing bit of conversation, I more or less offer to look at his work should he ever want to show it to me. I want to report that I gave him my business card but I don’t think I even had a business card from Tulane at that point. At any rate, he had my license and knew my name. But I never heard from him. I have no idea if the voice was ever matched to a character on the page, or if the pages ever amounted to a manuscript, let alone a book. But I think about this guy, sometimes. I think about the way he looked wistfully down dark and empty Rampart Street and sighed after he told me about the book, as though his character was supposed to meet him on this very corner but was, once again, a no-show.

He didn’t give me a ticket.