Academically, I did not know how to study in a university setting, as my inner-city high school in Jersey City, New Jersey, did not focus on preparing students for the rigors of a major university curriculum.

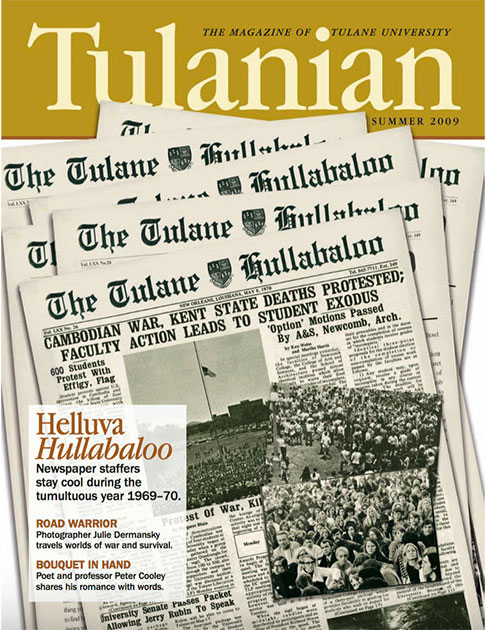

Ironically, the protests against the Vietnam War during the spring of 1970 saved me from being academically dismissed. In my first semester, the only “B” that I received in my five courses of Calculus, German, Physics and English was in Architecture, a five-credit course. In the second semester, I dropped German, so I managed to do a bit better.

Then, when all looked very bleak, on May 4, 1970, the Kent State massacre occurred wherein unarmed students protesting the war were killed by National Guardsmen in Ohio. When asked my opinion by my roommates in Phelps House, I responded that since no National Guardsmen were wounded, it was a failure of the officers’ command and control and was manslaughter by the government. Nationally, as an immediate result of Kent State, many universities shut down for the semester, including Tulane. That occurred one week before finals. I was sure that if I had taken the finals, I would have dropped out of Tulane. I survived to return for the fall 1970 and became more successful academically. In my first semester of the fourth year, I had a 3.75 GPA. In my final year, I won the Thomas J. Lupo award for my architectural thesis.

I lived in the dorms for all of my five years, and was a senior adviser in Sharp, and then Monroe halls. I made many wonderful friends. I witnessed the burning of the ROTC barracks on Freret Street, and the streaking craze in 1972. My wife, Emilia, and I were at the first football win over LSU in 25 years in 1973 ... a momentous event! We had many dorm-sponsored 50-cent banana split parties in Sharp on the third-floor lobby that all participants remember, including the football players.

My combat Marine unit of approximately 1,200 men, India Company, 3rd Marine Division, the 3rd Battalion / 4th Marines, sustained 88 percent casualties during the 12 months of 1968: 187 killed and 871 wounded. That percentage was typical of Marine infantry battalions in 1968, as we were in constant combat for the entire year. Panel 35 East on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C., lists 20 of my fellow Marines who were killed in the same four-day battle in which I was wounded.

The Vietnam Conflict and My Path to a Tulane Education

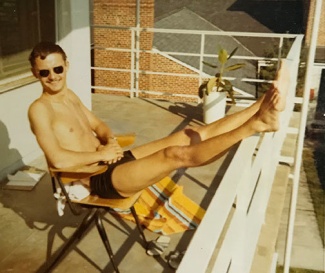

My experience at Tulane was amazingly unique, as I saw both sides of the Vietnam War coin. I had been wounded in combat alongside tough, courageous Marines. Twenty months later, I was at Tulane among America’s elite and privileged youth, witnessing the weekly protests against the war. Looking back, each experience was equally invaluable toward my maturity.

My experience at Tulane was amazingly unique, as I saw both sides of the Vietnam War coin. I had been wounded in combat alongside tough, courageous Marines. Twenty months later, I was at Tulane among America’s elite and privileged youth, witnessing the weekly protests against the war. Looking back, each experience was equally invaluable toward my maturity.

As a freshman at Tulane in fall 1969, I was “a fish out of water” both academically and socially. The years 1969–70 were the height of the Vietnam War protests. Among the other roommates in Phelps House room 333, I was a social aberration as a combat-wounded Marine. I had been nearly killed on Jan. 25, 1968, as an 18-year-old U.S. Marine infantryman in Vietnam.

For five years, most of my architectural classmates had no idea that I had been wounded in combat. Early in my freshman year in Phelps House, about six fellow students questioned me about my Vietnam experience. I described how one manages to get wounded, with dates, places and presentation of scars, but quickly realized that they seemed to be dismissive to the physical and psychological trauma of combat in Vietnam. One student asked why I would go to Vietnam when I was smart enough to be accepted at Tulane. The conversation left me to feel a fool for joining the Marines. At that moment, I decided that there will be no more discussions about Vietnam. Topics of heroism, patriotism and sacrifice for your country were anathema at Tulane in 1970. I would now focus on architecture and get on with my life. I never watched a single evening news broadcast about Vietnam during my years at Tulane.

"I was wounded in combat alongside tough, courageous Marines. Twenty months later, I was at Tulane among America’s elite and privileged youth, witnessing the weekly protests against the war.Looking back, each experience was equally invaluable toward my maturity."

Eugene M. Ogozalek, A ’74

This year, 2019, I will be an emeritus member of the American Institute of Architects, having been a member for 41 years. My company is named Willow Design Inc., as both Phelps House and Tulane Stadium were on Willow Street. One sports announcer at the time called the Tulane football team “The Willow Street Boys.”

Willow has designed expansions on VA hospitals across the country, including those in Oregon, Montana, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, South Carolina, New York and Pennsylvania. Most recently, Willow was one of 25 consultants on the brand-new, $2 billion New Orleans VA hospital on Canal Street, and on the $7 billion new headquarters for the Department of Homeland Security in Washington, D.C. I currently have architectural design work at the Charleston, South Carolina, VA Medical Center.

Belatedly, I wish to express my appreciation and sincere gratitude to Tulane (especially the acceptance committee of 1968 in the School of Architecture) for taking a chance on me. My Vietnam combat experience taught me to persevere under extreme circumstances. That was a lifelong lesson that served me well at Tulane.

The best five years of my life were at Tulane. I am a very lucky person.

Eugene M. Ogozalek (American Institute of Architects, National Council of Architectural Registration Boards) lives in Scranton, Pennsylvania.