(Photography by Paula Burch-Celentano)

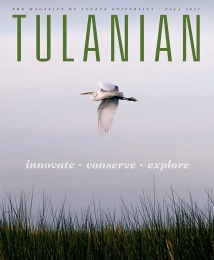

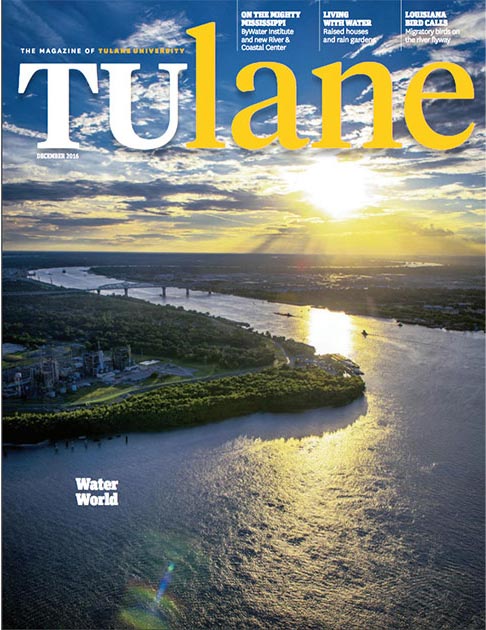

When cities face extreme weather brought on by climate change, finding the right solution can be as unpredictable as the rainfall. The complex relationships between government, geography, the built environment and community members are unique to regions. But Tulane faculty approach water management in new ways, upending old thinking about how to deal with it and how it affects communities.

Margarita Jover, Jesse Keenan and Joshua Lewis, each with their own expertise on water and climate-related issues in urban environments, know well the peril and promise of the world’s most plentiful resource. The trio recently shared their insights on how our relationship with water is changing and ways in which we can — and already are — adapting.

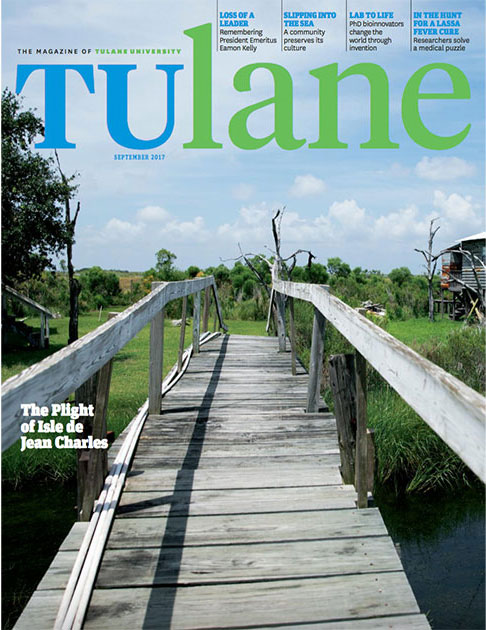

“Environmental change is not new in coastal Louisiana. That’s an inherent aspect of this place. It is constantly changing, shifting; it’s al ways growing; it’s always degrading,” said Joshua Lewis, research associate professor and research director at the Tulane ByWater Institute.

And with those changes, we need to adapt, or as Lewis describes it: “We need to live in the rhythms of Louisiana.”

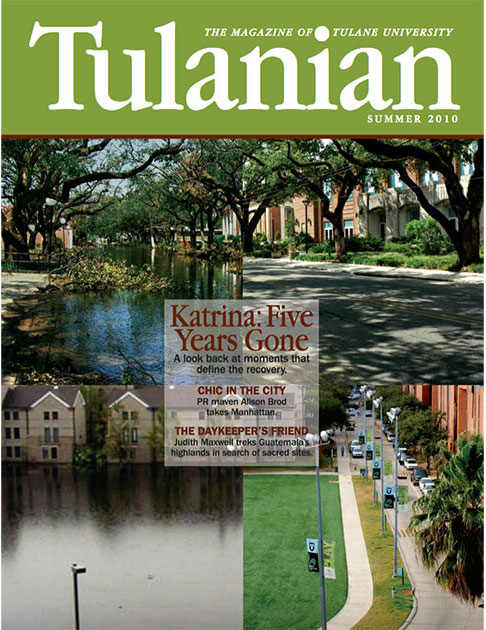

New Orleans might experience three types of flooding: riverine from the Mississippi River, precipitation-induced from a rainstorm or hurricane, and storm surge.

All are concerning on their own but what is more concerning is when these types combine with one another. Hurricane Katrina brought storm surge flooding to the city, and since then, the levees, gates and storm surge barriers have been improved. Now, though, there is more to consider.

“What we don’t know is what happens if the river flooding season lasts longer and it starts to overlap with hurricane season. And then we get a big storm surge event at the same time as we get river flooding,” Lewis said.

Hurricane Barry, a Category 1 hurricane that made landfall in Louisiana in July 2019, is an example of a hurricane occurring when Mississippi River levels had been elevated for a prolonged period. Barry, with 75-mile-per-hour winds at its strongest, dropped heavy rainfall. But the Mississippi River levees easily held as they are designed to do.

Precipitation-induced street flooding, even without a hurricane, is the type of flooding New Orleanians are accustomed to seeing — especially lately.

“That alone has emerged as the most day-to-day regular type of event — with its increased frequency and intensity — that we’re not really equipped to deal with,” Lewis said.

Historically, the city has used canals and pumps to get water out of the city as quickly as possible. However, Lewis said there are limitations with that type of drainage system.

“We understand that it causes the land to subside. As you continually pump out all this water, and you drain swampy areas, you get subsidence and compaction, and that’s what creates this below-sea-level situation.

“That’s the big issue. That it’s too much water too fast,” he said.

Following the unprecedented 2020 hurricane season, in which five named storms made landfall in Louisiana, breaking the state record for a single season, and with other more frequent severe weather events expected, Lewis is looking to manage water in new ways.