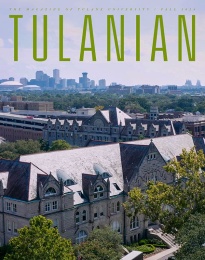

Above: A man walks his dog on the Mississippi River levee near Oak Street in New Orleans in March 2018 when the river’s level had risen above 15 feet. (Photo by Paula Burch Celentano)

There’s a new department at Tulane in the School of Science and Engineering that’s addressing some of the most existential issues of our time: rising sea levels and sinking land.

Professor and Chair Mead Allison’s work on the flow of sediment and water through riverine and deltaic coastal systems underpins the four-year-old Department of River-Coastal Science and Engineering. So does the research and educational leadership of Professor Ehab Meselhe, Research Professor Barbara Kleiss and others.

The new department offers a blending of basic science and applied science with an interdisciplinary approach that gives students the tools, knowledge and understanding to make real-world connections in communities and attack real-world research-oriented problems.

“This new generation of students is all about solving practical problems,” said Allison.

A five-year Bachelor of Science in Environmental Engineering and Master of Architecture in Landscape that Allison has proposed, along with Iñaki Alday, dean of the School of Architecture, could be a departmental offering soon. Graduates of that program would be grounded in the principles of science and engineering and would gain experience participating in an architectural design studio.

“These are the kinds of novel things that are starting to roll out of this department that are only going to snowball as our faculty increases,” said Allison. With this program, “what we’ve done is bring back elements of an environmental engineering program that we had at Tulane, but it’s packaged in a very 21st-century way.”

“We’re going to be a very specialized department,” he added. “We’re focusing on a certain area of the Earth.”

That area of the Earth — rivers and coasts — is more than the Gulf Coast of the United States.

“Certainly, the Gulf Coast is in the front trenches,” said Allison, “but there are communities around the world in the front trenches.” These include mega cities of more than 10 million in population, such as Jakarta, Indonesia, and Dhaka, Bangladesh, located in endangered coastal zones, and Mexico City, vulnerable to flooding. In some cases, these cities are in deltas like New Orleans and are particularly at risk from rising sea levels and subsidence.

A sediment deposit map, created by Ehab Meselhe’s lab group through computer modeling, predicts the effects of the proposed Mid Barataria sediment diversion project.

A sediment deposit map, created by Ehab Meselhe’s lab group through computer modeling, predicts the effects of the proposed Mid Barataria sediment diversion project.