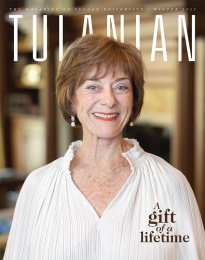

Above photo: Kim Vaz-Deville holds a portrait by Meryt Harding. (by Paula Burch-Celentano)

As a child, Kim Vaz-Deville (NC ’81, G ’83) spent many hours at her grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ double on North Claiborne Avenue in New Orleans, and she remembers vividly the hustle and bustle of that vibrant neighborhood. Growing up in the ’60s and ’70s, Vaz-Deville experienced the rise of African American political and social power, but also witnessed the devastation of the Claiborne Avenue community that resulted from the construction of Interstate Highway 10. She recalls sadly how Mardi Gras masking traditions waned within the black community.

After completing undergraduate and graduate work at Tulane, Vaz-Deville earned her PhD from Indiana University, and is now a professor of education and associate dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at Xavier University of Louisiana. As a feminist scholar, she has contemplated the ways in which African American women have created their own traditions and made a mark on New Orleans.

Vaz-Deville became particularly interested in the Baby Dolls, groups of working-class women who began masking for Carnival around 1912. Dressed in baby doll costumes of short dresses, garters and bonnets, these women would strut and shake as they walked down the street, singing bawdy songs. They defied social norms and the traditional perception of the place of women of color in society.

“You could contrast [the Baby Dolls] with black people’s [customary] participation in Mardi Gras as servants at balls and as flambeaux carriers … they weren’t allowed to go on Canal Street, so they made their own Mardi Gras,” Vaz-Deville said.

Vaz-Deville’s curiosity about these strong, defiant women led her to write The Baby Dolls: Breaking the Race and Gender Barriers of the New Orleans Mardi Gras Tradition (2013). The book explores the Baby Doll tradition and its evolution to the modern day.

The Louisiana State Museum also presented an exhibition, “They Call Me Baby Doll: A Mardi Gras Tradition,” at the Presbytere in 2013, based on Vaz-Deville’s research. This collaborative spirit led to Vaz-Deville’s 2018 publication, Walking Raddy: The Baby Dolls of New Orleans, a collection of essays and visual art by New Orleans scholars and artists.

Traditionally, masking groups only came out for Mardi Gras and St. Joseph’s Night, but today there are over a dozen Baby Doll groups who also participate in Jazz Fest, Satchmo SummerFest, funerals and parties. As a new generation of Baby Dolls revives the tradition in New Orleans, Vaz-Deville sees connections that are meaningful for this century.

“It’s a new cultural era where people have more opportunities,” she said. “They are forming a sisterhood; they are there to support and celebrate each other.”