Dining on a meal of roast turkey, potato circles, semolina sticks and walnut cream cake, Steven Fenves marveled at the spread before him. “What I tasted was really terrific,” said the 93-year-old Auschwitz survivor, musing over the redolent flavors. “The semolina sticks were all very authentic.”

Fenves had stepped back in time, savoring the taste of his mother’s recipes for the first time in 80 years. The experience reconnected him to his childhood in Yugoslavia and awakened memories of a happy life before it was torn apart by World War II.

Collected in a tattered, cloth-bound ledger book, the recipes were almost lost forever. Rescued by the family’s cook in May 1944 as Fenves, his sister and their parents were deported to concentration camps, the recipe book likely would have remained a dusty artifact in the collection of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum if not for the work of Emily Shaya (B ’06, B ’13), her husband, chef Alon Shaya, and their friend Mara Baumgarten Force, professor of practice at the A. B. Freeman School of Business at Tulane University.

Their discovery of the recipe book in 2019 set in motion an inspirational journey that has reenergized Fenves and put his family’s long-lost recipes back on dinner tables. The Shayas and Force dubbed their effort Rescued Recipes.

“Generations of family histories and family traditions were obliterated during the Holocaust,” says Force, whose grandparents were Holocaust survivors. “This project reanimates and gives life to that past.”

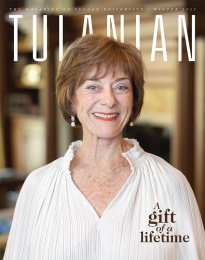

As Director of New Projects at Pomegranate Hospitality, the restaurant group she owns with Alon, Emily Shaya sits at the helm of an organization that has garnered local and national accolades. In 2015, Alon won the James Beard Award for Best Chef in the South, and in 2016, he won the James Beard Award for Best New Restaurant in America.

Beyond their culinary success, the Shayas are also involved in a host of public service activities, including partnering with local nonprofits to educate young culinary workers and donating thousands of dollars to local charities.

“We can’t just be off by ourselves,” Emily says of their service activities. “It’s really important for us to have a relationship with the New Orleans community.”

Emily’s relationship with New Orleans began in 2002 when she arrived from Calhoun, Georgia, as a first-year student at Tulane University. After graduating in 2006 with a Bachelor of Science in Management, she landed a job with Woodward Interests, a New Orleans-based development company.

Overseeing real estate projects may seem a far cry from managing restaurants, but Emily drew on that experience when she entered the hospitality industry. In 2017, she and Alon, whom she married in 2012, founded Pomegranate Hospitality. A year later they opened two modern Israeli restaurants: Saba in uptown New Orleans and Safta in Denver. “Really, those restaurants were real estate development projects,” Emily says. “I took that real estate expertise and applied it to the first two restaurants we opened.”

Following the success of Saba and Safta, the Shayas partnered with the Four Seasons Hotel in New Orleans to open Miss River and the Chandelier Bar. In 2023, they introduced another restaurant, Silan, at the Atlantis Paradise Island Resort in the Bahamas, and in 2024 they launched Safta 1964, a limited-run celebrity-chef residency at The Wynn Las Vegas. They plan to open Safta’s Table soon in New Orleans’ Lakeview neighborhood.

In running Pomegranate Hospitality, Emily’s business mindset complements Alon’s culinary focus. While Alon oversees menus and food production, Emily makes hiring decisions, supports staff and develops partnerships to advance the company’s philanthropic goals.

Each year, the Shayas host a fundraiser to benefit the New Orleans Career Center, whose culinary program provides career training for students entering the hospitality sector. Emily and Alon also support up-and-coming restaurateurs through the Shaya Barnett Foundation, created with Alon’s mentor Donna Barnett, which offers educational opportunities for students looking to work in the food and beverage industry.

“What Emily is doing in her businesses is an extension of the service-learning we teach here at Tulane,” says Force, “and it’s fantastic to see.”

When she’s not laying the groundwork for future Pomegranate Hospitality ventures, Emily oversees the minutiae that make for a memorable dining experience. “The way people feel when they’re in the restaurants is really important to us,” she explains. “And it all boils down to the finishing touches.”

“With everything we do,” adds Alon, “there’s meaning and a story behind it.”

Stories are served in abundance at their restaurants. Saba’s name, Hebrew for grandfather, calls to mind paternal stories passed down between generations. Dishes like matzo ball soup, lamb kofta and tahini hummus evoke Alon’s youth in Israel, where he lived until he was four years old. Miss River tells a different story, one that begins much closer to the couple’s present-day home. The restaurant draws inspiration from Southern culinary traditions and Emily’s Georgia upbringing, with a menu boasting everything from Emily’s red beans and rice to butter-fried beignets.